Bukit Larangan: Early Singapore in Maps, Texts, and Artifacts

Located at the junction of Canning Rise and Fort Canning Road, Fort Canning Hill, Fort Canning Hill has a rich history that spans several centuries. Originally known as Bukit Larangan, or the “Forbidden Hill” in Malay, the 48-metre hill is believed to be the site where the first kings of the island resided during the 14th century. The hill is also rich in archaeological finds, and the discovery of artefacts such as earthenware pottery, coins, and Chinese ceramics indicated that the island was already a trading center actively engaging in commerce with neighbouring ports and regions even before the arrival of the British in 1819. This pre-colonial period of Singapore’s history is also recorded in other historical sources, including texts and maps.

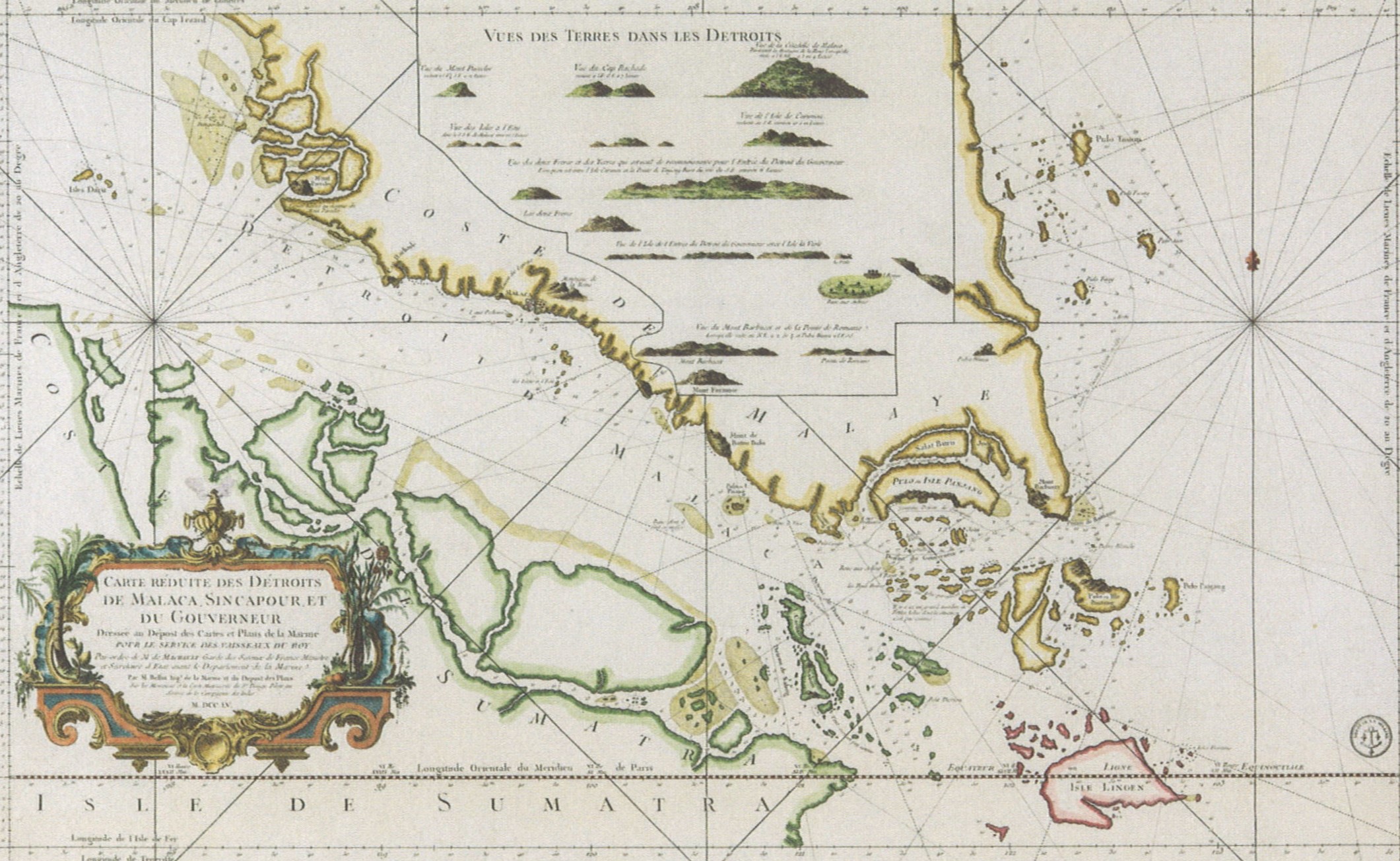

Early Singapore in Maps

The National Library in Singapore houses a collection of rare maps dating back to the 15th century. This collection includes topographic maps and navigational charts that cover Singapore and the surrounding region. Most of these maps were printed by European map-makers, and they provide valuable insights into the historical significance of various locations, including pre-colonial Singapore.

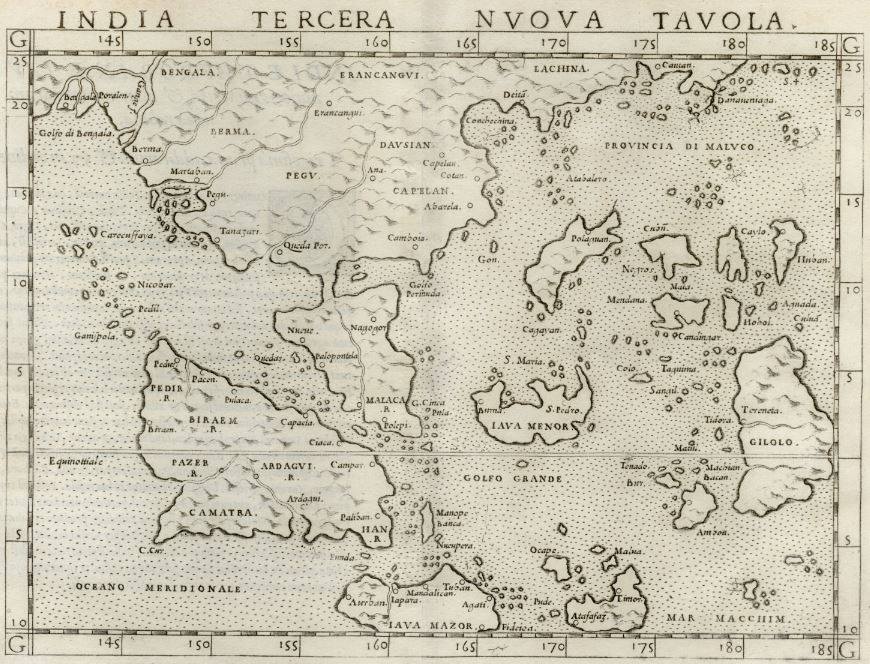

|

| The National Library of Singapore’s map collection includes the 1561 map titled India Tercera Nuova Tavola, which is among the oldest surviving maps of Southeast Asia from the early modern period. The map references “Cinca Pula” near the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, which scholars believe refers to the island of Singapore. Created by the Italian cartographer Girolamo Ruscelli, the map is composed of two sheets of paper seamed together. It was drawn during a time when European traders were exploring new routes to the East of India, including the Spice Islands in Southeast Asia. This historical map can be accessed digitally via NL Online. (Image Credit: Collection of National Library, Singapore) |

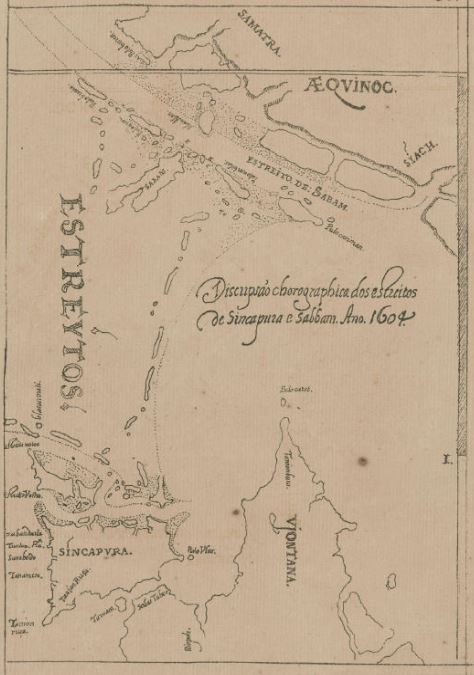

|

| Manuel Godinho de Erédia, a Malacca-born Portuguese-Bugis naval commander, created a map in 1604 titled Discripsao chorographica dos estreitos de Sincapura e Sabbam, ano 1604 (Chorographic Description of the Straits of Sincapura and Sabbam 1604 A.D). This map is part of a larger work and is one of the earliest surviving maps to depict pre-colonial Singapore. In the map, Singapore is referred to as ‘Sincapura,’ and locations such as Blakang Mati (now Sentosa), Tanjong Rhu, Sungei Bedok, Tanah Merah, Tanjong Rusa, and Selat Tebrau are also shown. The name “Xabandaria” is marked near the west of Tanjong Rhu, indicating the presence of a ‘Shahbandar’ or harbor master’s compound on the island. This historical map, which is shown here, can be accessed digitally via NL Online. (Image Credit: Collection of National Library, Singapore) |

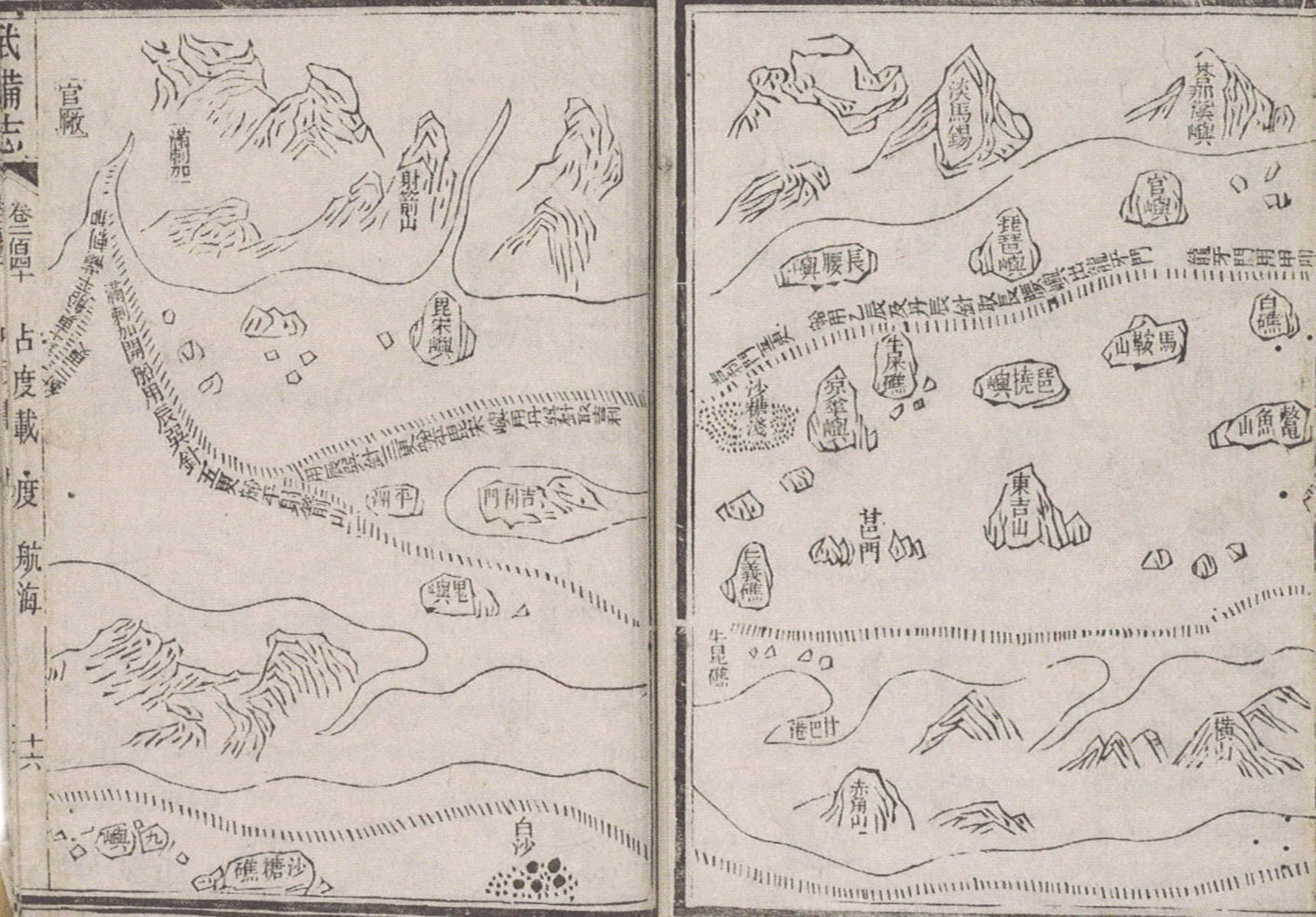

|

| The Mao Kun Map (茅坤图) is a set of navigational maps based on the expeditions of Ming dynasty diplomat Admiral Zheng He in the 15th century. Also known as Zheng He’s Navigation Map (郑和航海图) or the Wu Bei Zhi Chart, it was likely drawn between 1425 and 1430 and published in the late-Ming publication Wu Bei Zhi (武备志). The map was compiled by Mao Yuanyi (茅元仪; 1594–1640), a strategist in the Ming court, in 1621 and published in 1628. The maps depict the return route between Melaka and China through the Strait of Singapore and include the name “Temasek” (淡马锡), marked on a hill on the right page, while “Malacca” (满剌加) is labelled at the top left of the left page. The Mao Kun Map can be accessed digitally via NL Online. (Image Credit: SFFCCA Collection, Courtesy of National Library, Singapore) |

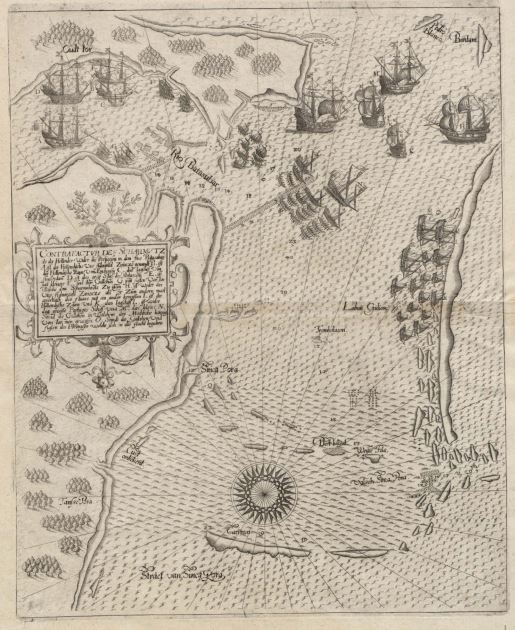

|

| This 1606 schematic map depicts the battle between the Portuguese and the Dutch from 6 to 11 October 1603, fought off the southeastern coast of Singapore at the Johor River. Drawn with the east oriented to the top, the map is titled Contrafactur des Scharmutz els der Hollender wider die Portigesen in dem Flus Balusabar (Chart of a Skirmish between the Dutch and the Portuguese in the Balusabar River) and was published by the De Bry family, a well-known family of cartographers, engravers, and publishers. In the map, Singapore is spelled “Sinca Pora”, and it is one of the earliest representations of the island’s coastline. Furthermore, the map shows the Johor Fleet (who were allies of the Dutch) waiting at a shoal off the eastern coast of Singapore. This map is significant as it illustrates the strategic importance of the Singapore Strait as a waterway connecting the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea. This map can be accessed digitally via NL Online. (Image Credit: Collection of National Library, Singapore) |

|

| Jacques Nicolas Bellin (1703–72) was a French hydrographer who created maps for several key publications in the 18th century. In this 1755 map, Bellin depicted Singapore as an elongated island, calling it “Pulo or Isle Panjang” which means “Long Island” in Malay. He also indicated that the “Vieux Detroit de Sincapour” (or “Strait of Singapore”) includes the water channel that separates Singapore Island from the Malay Peninsula. Today, this strip of water is known as the Johor or Tebrau Strait. This map can be accessed digitally via NL Online. (Image Credit: Collection of National Library, Singapore) |

Early Singapore in Texts

Historical texts constitute another source of information pointing to the existence of a pre-colonial Singapore. Among them, Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings), better known as Sejarah Melayu or Malay Annals, and Wang Dayuan’s (汪大渊) Daoyi Zhilue (岛夷志略; A Description of the Barbarians of the Isles) are the two most well-known. Produced in the 17th century and 14th century respectively, they provide a rare glimpse to the life, trade, people and culture of pre-1819 Singapore.

|

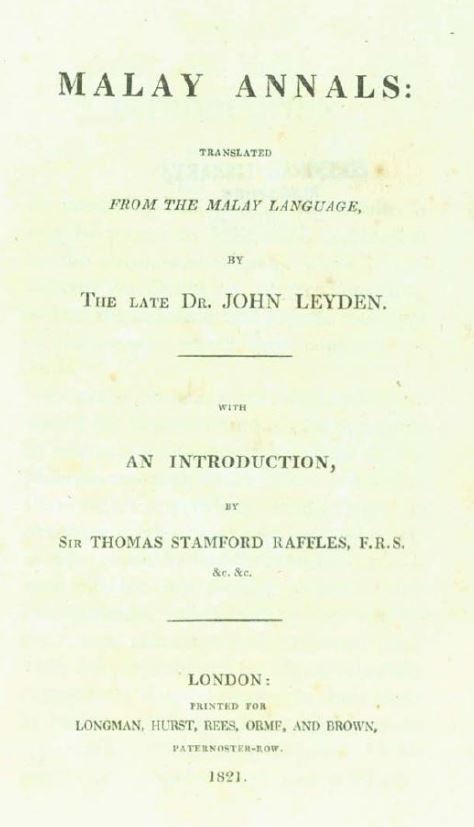

| The 17th-century Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings), better known as Sejarah Melayu or Malay Annals, is one of the most important Malay historical works. It is a collection of stories covering the Malaccan sultanate. For Singapore, this work is significant because it also contains stories of the island including Sang Nila Utama’s naming of Singapore as “Singapura” (“Lion City” in Sanskrit), adventures of the mighty Badang, the mythical garfish attack and the flight of the last king of Singapura fled to Malacca in 1389, where he founded the Malacca Sultanate. The first English translation of the Sejarah Melayu was published posthumously by John Leyden in 1821 as The Malay Annals, while the Jawi text by Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir Munshi in 1840. Shown here is the 1821 title page of Leyden’s work available in NL Online. (Image Credit: All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore) |

We all grew up with the story of how Sang Nila Utama, a Palembang prince from the Srivijaya ruling house, founded "Singapura", or “Lion City”, through the sighting of a lion on the island. This tale from the 13th century is included in one of the oldest and most important Malay texts, Sejarah Melayu or the Malay Annals. Click or tap HERE to read the account of the sighting from the Malay Annals (1821) (pp. 42-44). (Source: Call no.: RRARE 959.7 CRA or NL Online)

"Then Sang Nila Utama reached a stone of great height and size, on which he mounted and viewed the opposite shore, with its sands white as cotton; and enquiring what sands were these which he saw, Indra B’hupala informed him they were the sands of the extensive country of Tamasek. The prince immediately proposed to visit them…But as they were passing over, they were caught in a severe storm, and the vessels began to leak, and the crews were unable, after repeated exertions, to throw out the water. They were accordingly compelled to throw overboard the greater part of the baggage in the vessel…The water nevertheless continued to gain ground, and every thing was thrown overboard till nothing now remained except the diadem…The prince ordered the diadem to be thrown overboard, the storm ceased and the vessel rose in the water, and the rowers pulled her ashore, and Sang Nila Utama with his attendants, immediately landed on the sands, and went to amuse themselves on the plain near the mouth of the river of Tamasek. There they saw an animal extremely swift and beautiful, its body of a red colour, it head black and its breast white, extremely agile, and of great strength, and its size a little larger than a he-goat. When it saw a great many people, it went towards the island and disappeared. Sang Nila Utiama enquired what animal was this, but none could them, till he enquired Damang Lebar Dawn, who informed him that the histories of ancient time, the sangha or lion was described in the same manner as this animal appeared. This is a fine place which contains so fierce and powerful an animal. Then Sang Nila Utama directed Indra B’hupala to go and inform his mother-in-law, that he should not return…and thus Sang Nila Utama settled the country of Tamasak, named it Singhapura, and reigned over it, and was panegyrized by Bat’h, who gave him the name of Sri Tri-buana."

|

| Besides the story of Sang Nila Utama and how he founded Singapura, the Malay Annals also contain many other tales that Singaporeans are quite familiar with growing up. These include the strong man Badang and the attack of the garfish. As such, this work continues to enchant Singaporeans as well as writers and readers everywhere. Over the recent decades, many authors have brought these timeless stories from the ancient manuscript to the masses using a myriad of creative adaptions ranging from comic strips to children’s books. Shown here is an example by Hidayah Amin and Eliz Ong. Titled, The Malay Annals: Attack of the Garfish and Other Adventures (2021) (Call no.: Junior Reference S823 HID), you can find it in our public libraries. (Image Credit: All rights reserved, The Malay Annals: Attack of the Garfish and Other Adventures, 2021, Amin Hidayah and Ong, E., Singapore: WS Education) |

Click or tap HERE to read an excerpt of the Garfish Attack taken from Hidayah Amin's and Eliz Ong's The Malay Annals: Attack of the Garfish and Other Adventures (2021) (pp. 52-54). (Source: Call no.: Junior Reference S823 HID)

"A small voice then said to the King, “Your Majesty, why not use banana trunks instead?" The voice belonged to a boy who looked like he was seven years old. The boy, known as Hang Nadim, had been watching from afar. It was not common for a king to take advice from children. However, as the King was desperate to save Singapura, he agreed to try out Hang Nadim’s suggestion. He instructed his men to cut down banana trunks and erect them side by side on the shoreline to form a fence. Woosh! Woosh! Woosh! The garfish launched wave after wave of attack. Only this time, their jaws got stuck onto the banana trunks. They could not escape. “Go! Kill the enemies!” bellowed the King victoriously. Charging forward, the King’s men killed the wriggling garfish. Singapura was finally saved."

|

| Wang Dayuan, the intrepid 14th-century traveller from Quanzhou, China, was the first Chinese to write extensively about Southeast Asia based on his personal experiences and published them in Dao Yi Zhi Lue (岛夷志略 or “Description of the Barbarians of the Isles in Brief”) in 1350. In the work, Wang mentions three place names in conjunction with Singapore. The first is “Dan Ma Xi” (“淡马锡” or “Temasek”), which refers to the general area of Singapore and the nearby islands. The second is “Longyamen” (龙牙门 or “Dragon’s Tooth Strait”), a place now identified as the waterway between what is now Sentosa island and Labrador Point. The third is “Banzu”, which is believed as a transliteration of the Malay word “pancur”, meaning “spring of water” and a reference to today’s Fort Canning Hill. Wang Dayuan’s account of Singapore has been translated several times; the most commonly available translation is by Paul Wheatley’s The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the historical geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500 (Call no.: RSING 959.5 WHE). (Image Credit: All rights Reserved, The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the historical geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500, 1961, Wheatley, P., University of Malaya Press, Kuala Lumpur) |

Wang Dayuan’s account of Singapore has been translated several times; the most commonly available translation is by Paul Wheatley’s The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500. Click or tap HERE to read it. (Source: Call no.: RSING 959.5 WHE)

"The strait runs between the two hills of the Tan-ma-hsi barbarians, which look like ‘dragon teeth’. Through the centre runs a waterway. The fields are barren and there is little padi. The climate is hot with very heavy rains in the fourth and fifth moons. The inhabitants are addicted to piracy. In ancient times, when digging the ground, a chief came upon a jewelled head-dress. The beginning of the year is calculated from the [first] rising of the moon, when the chief put on his head-gear and wore his [ceremonial] dress to receive the congratulations [of the people]. Nowadays this custom is still continued. The natives and the Chinese dwell side-by-side. Most [of the natives] gather their hair in chignons, and wear short cotton bajus girded about with black cotton sarong. Indigenous products include coarse lakawood and tin. The goods used in trade are red gold, blue satin, cotton prints, Ch’u [chou-fu] porcelain, iron caldrons and suchlike things. Neither fine products nor rare objects come from here. All are obtained from intercourse with Ch’üan-chou traders. When junks sail to the Western Ocean, the local barbarians allow them to pass unmolested but when on their return the junks reach Chi-limen (Karimon), [then] the sailors prepare their armour and padded screens as a protection against arrows for, of a certainty, some two or three hundred pirate prahus will put out to attack them for several days. Sometimes [the junks] are fortunate enough to escape with a favouring wind; otherwise the crews are butchered and the merchandise made off within quick time"

Early Singapore In Artefacts

At the inception of a British settlement in Singapore in 1819, Sir Stamford Raffles and John Crawfurd, the second British Resident of Singapore, found many vestiges of a much older settlement. However, it was not until 1984 when the first proper archaeological investigation was carried out. Initiated by the National Museum and led by Professor John Miksic, artefacts dating back to the period between 1300 and 1600 were recovered, providing further evidence of the existence of a pre-colonial Singapore.

|

| The Singapore Stone is a sandstone slab inscribed with an ancient script that once stood at the mouth of the Singapore River. According to an 1825 map, the original location of the Singapore Stone was at Rocky Point, near present-day Fullerton Hotel. It was approximately 3 meters high and 3 meters wide, and it was said to contain about 50 lines of inscription. However, it was blown up in 1843 under the orders of the settlement engineer, Captain Stevenson, to provide space for Fort Fullerton and its living quarters. In 1848, parts of the stone were sent to Kolkata in India for study, while the rest of the stone, shown here, remains in Singapore and is currently on display at the National Museum of Singapore. Scholars believe that the ancient script is likely to be either Old Javanese (Kawi) or Sanskrit and might date back to the 11th to 14th centuries. (Image Credit: Courtesy of the National Heritage Board) |

|

| In 1928, 10 ancient gold ornaments said to be related to the Majapahit Empire were discovered during the construction of the Fort Canning Reservoir. These items could have been hidden during a Siamese attack at the end of the 14th century. Only four ornaments remained after the Japanese Occupation; the whereabouts of the other six are unknown. Shown here is one of the ornaments. (Image Credit: Courtesy of the National Heritage Board) |

|

| In 1984, Prof. John Miksic led an archaeological research project on Fort Canning Hill to investigate whether remains of ancient Singapore could be found. One of the excavation pits located near Keramat Iskandar Shah yielded two significant objects made of Chinese porcelain: a compass (shown here) and a porcelain pillow on which theatrical images were depicted. So far, the porcelain compass is the only known example of a Chinese porcelain compass. (Image Credit: All rights reserved, The Fort Canning Spice Garden Site Report, 2010, Goh, G. Y., and Miksic, J. N. [CC BY 4.0]) |

|

| Fort Canning has been excavated several times since the 1980s. During the construction of a wheelchair ramp at the Fort Canning Spice Gardens excavation, a blue glass bead (shown above) was found and is suspected to be from a 14th-century layer. At a nearby site located 25 meters to the west, 159 glass beads, as well as irregularly shaped globules (blobs), shards of thin-walled containers, and bangle fragments, were found during an archaeological excavation at the Fort Canning site in 1988. Based on the irregular shaped globules, the site was suspected to be a glass workshop. It was thought that the glass was either imported or produced locally. (Image Credit: All rights reserved, The Fort Canning Spice Garden Site Report, 2010, Goh, G. Y., and Miksic, J. N. [CC BY 4.0]) |

|

| This fragment of a green porcelain bowl (shown here) was excavated in 2010 on Fort Canning Hill, near the Fort Canning Spice Gardens. The fine quality of the porcelain suggests that it was likely a product from China, and its discovery provides further evidence that Fort Canning Hill may have been an area for elites during the 14th century. This artefact also highlights Singapore’s importance as a trading hub during that time. (Image Credit: All rights reserved, The Fort Canning Spice Garden Site Report, 2010, Goh, G. Y., and Miksic, J. N. [CC BY 4.0]) |

|

| On Fort Canning Hill, there is a keramat, or shrine that holds an old tomb (shown here). This tomb is said to contain the remains of Sri Sultan Iskandar Shah, the fifth and last ruler of precolonial Singapore. The site has been considered auspicious by many. It has undergone several phases of restoration over the years, with the most recent being the addition of a 14th-century Malay roof called a pendopo. The 20 wooden pillars holding up the roof are decorated with a fighting cock motif of Javanese origin. (Image credit: Photo by janebelindasmith via Wikicommons) |

The archaeological remains of early Singapore were also recorded by observers such as John Crawfurd. In his Journal of an Embassy to From the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China (1830), he recorded a description of the ancient walls of early Singapore. Click or tap HERE to read his description (pp. 68-70). (Source: Call no.: RRARE 959.7 CRA or NL Online)

"I walked this morning round the walls and limits of the ancient town of Singapore, for such in reality had been the site of our modern settlement. It was bounded to the east by the sea, to the north by a wall, and to the west by a salt creek or inlet of the sea. The inclosed space is a plain, ending in a hill of considerable extent, and a hundred and fifty feet in height. The whole is a kind of triangle, of which the base is the sea-side, about a mile in length. The wall, which is about sixteen feet in breadth at its base, and at present about eight or nine in height, runs very near a mild from the sea-coast to the base of the hill, until it meets a salt marsh. As long as it continues in the plain, it is skirted by little rivulet running at the foot of it, and forming a kind of moat; and where it attains the elevated side of the hill, there there are apparent the remains of a dry ditch. On the western side, which extends from the termination of the wall to the sea, the distance, like that of the northern side, is very near a mile, This last has the natural and strong defence of a salt marsh, overflown at high-water, and of a deep and broad creek. In the wall there are no embrasures or loop-holes; and neither on the sea-side, nor on that skirted by the creek and marsh, is there any appearance whatever of artificial defences. We may conclude from these circumstances, that the works of Singapore were not intended against fire-arms, or an attack by the sea; or that if the latter, the inhabitants considered themselves strong in their naval force, and therefore thought any other defences in that quarter superfluous."

Learn More About Professor John Miksic and the Archaeological Digs On Fort Canning Hill

Primary school history lessons teach that Sir Stamford Raffles founded modern Singapore in 1819. However, archaeological excavations at Fort Canning, led by Professor John Miksic from the National University of Singapore, and other archaeologists over the years, have shown that there was already a large and diverse community thriving on the island more than 700 years ago. So who is Professor John Miksic? Find out more in this video by the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) Singapore.

In addition, the National Museum of Singapore has a short video showcasing the key archaeological finds on Fort Canning Hill. Watch it here and learn what they are and their significance.