Roots in Nature

Jurong is an area in the southwest of Singapore, comprising housing estates such as Jurong West and Jurong East, as well as the innovation, business, and industrial estates of Jurong Lake District and the Jurong Innovation District, among others. It was a very different place before its development in the 1960s. Largely undeveloped, it was an area littered with villages, swamps, patches of jungle, and plantations, with numerous rivers, streams, and tributaries

Jurong in Early Maps of Singapore

The development of Jurong during its early days is documented in the Maps Collection of the National Library and National Archives of Singapore. You can observe its evolution by exploring the various historical maps from the collection shown below. To compare these changes and overlay them with present-day maps, you can utilise the Spatial Discovery platform.

|

| The 1828 map of Singapore by Captain James Franklin and Lieutenant Philip Jackson shown above is one of the earliest maps to accurately depict Singapore Island. It provides valuable information about the natural features associated with Jurong, highlighting the Jurong and Pandan rivers and identifies the islands that now collectively form Jurong Island, including Pulau Ayer Chawan, Pulau Seraya, and Pulau Sakra. The map also marks geographical features in the Tuas area, such as Tanjong Rawa (a promontory) and Tanjong Gull (Tanjong Gul). These details offer insights into the historical geography of the Jurong region. (Image Credit: Singapore Land Authority collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| The natural features of Jurong, including the Jurong and Pandan rivers, are also depicted on the 1855 hydrographic survey of the Straits of Singapore shown above. This survey, conducted by Captain Samuel Congalton and Government Surveyor John Turnbull Thomson, stands as one of the earliest comprehensive hydrographic surveys of the region carried out by a surveyor based locally. It provides a detailed and valuable portrayal of the geographical characteristics of the Jurong area. (Image Credit: Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

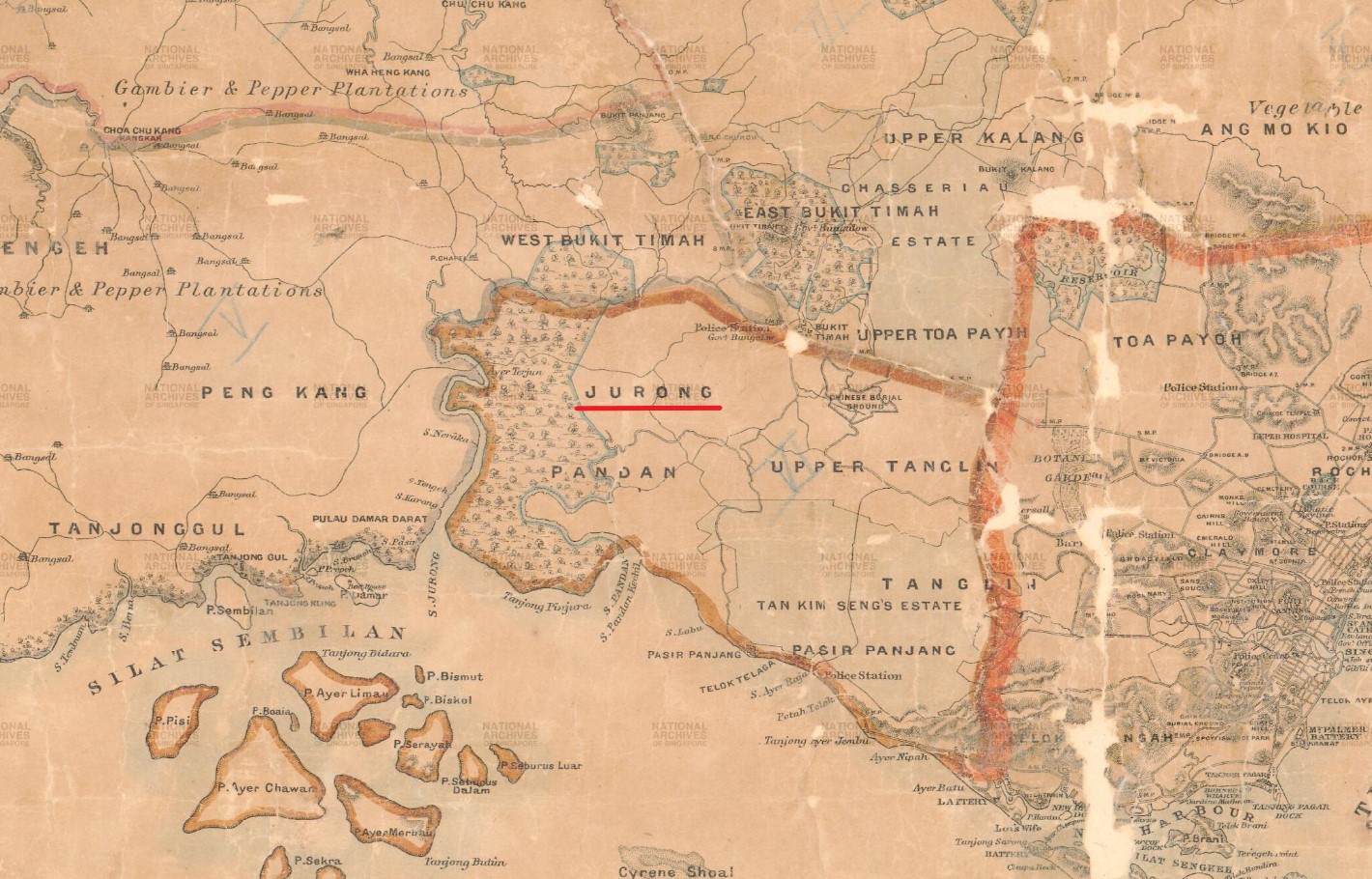

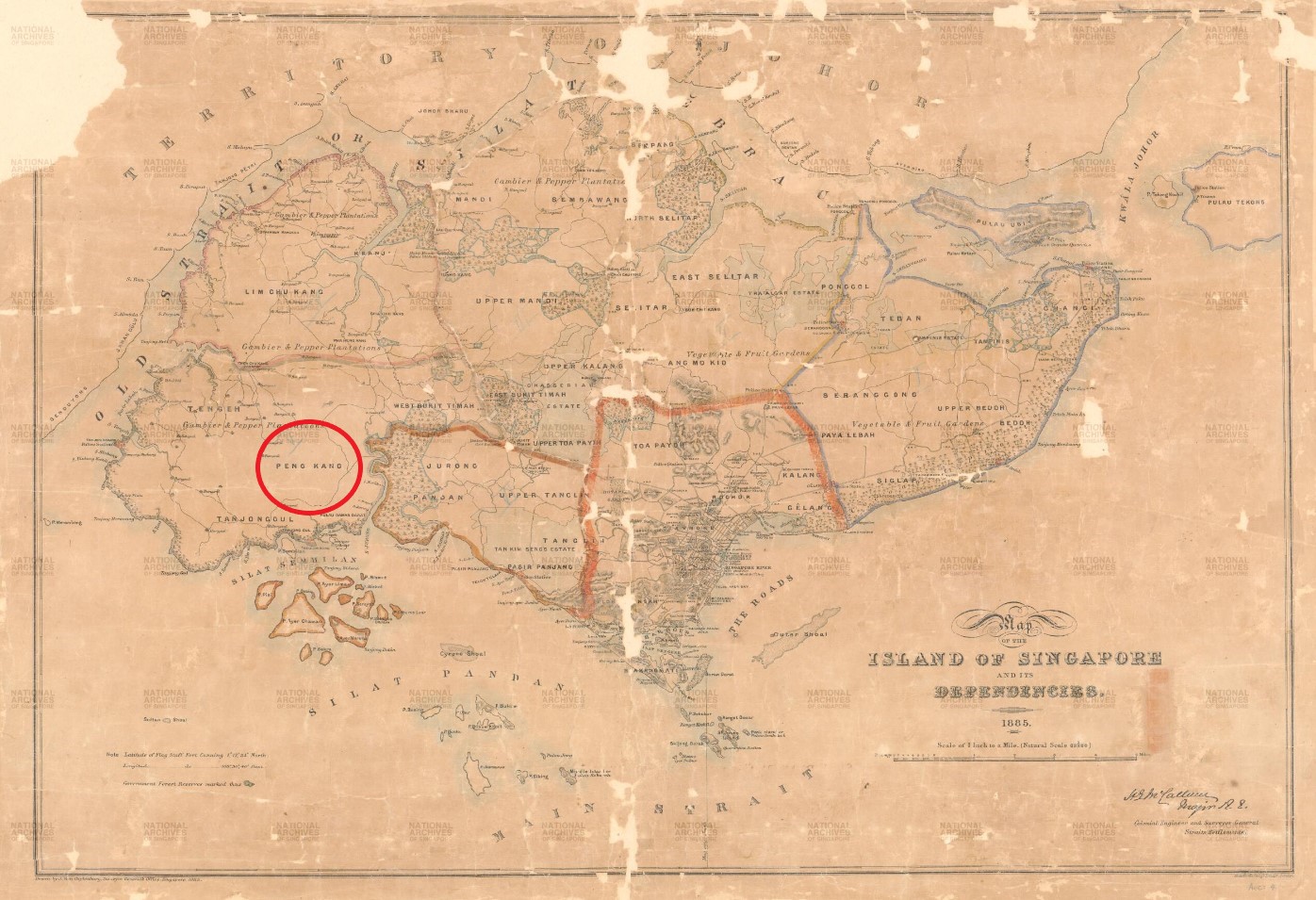

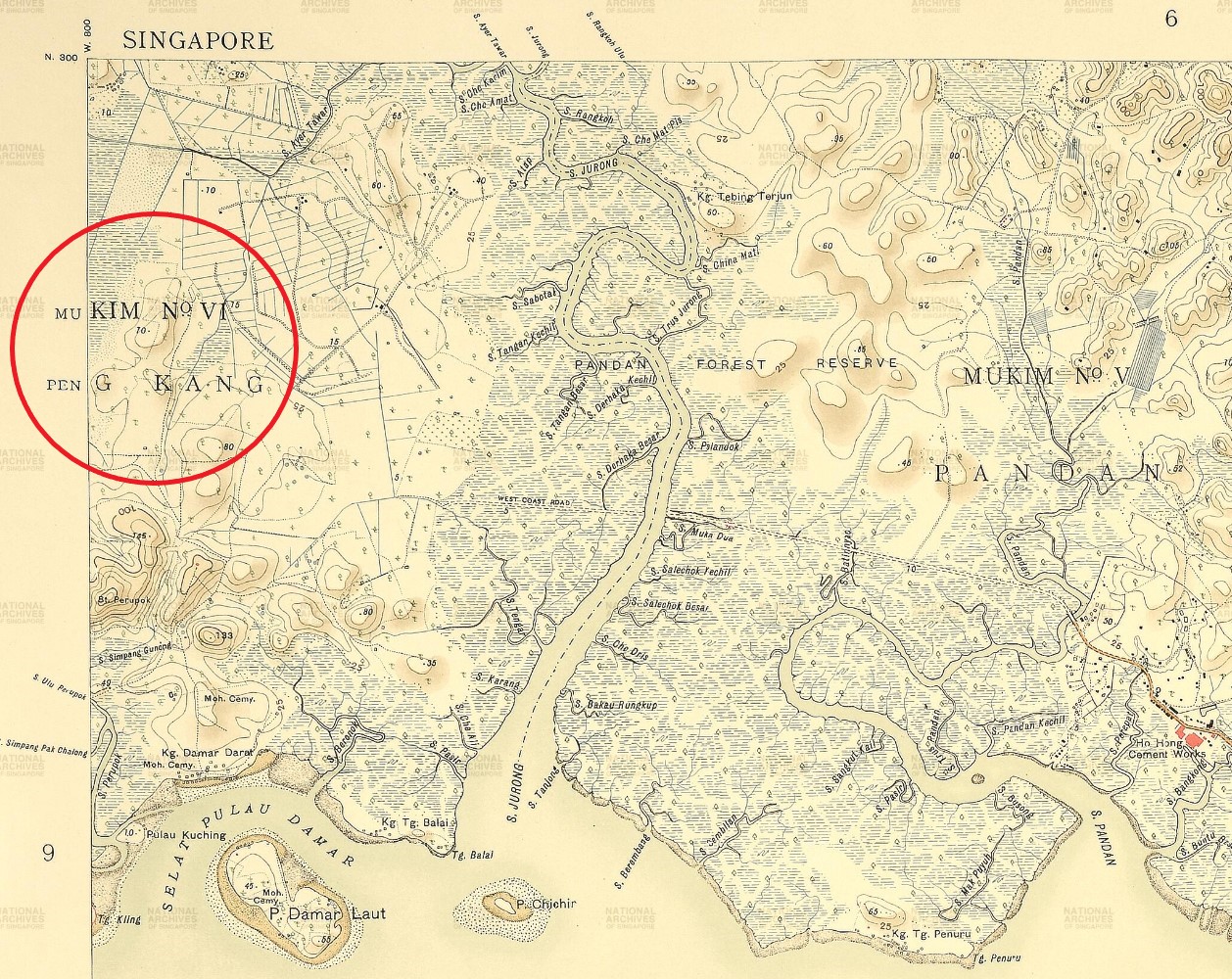

| While the early 19th-century maps of Singapore provide detailed information about the natural features of Jurong, maps from the later half of the 19th century and the early 20th century show a much smaller boundary for Jurong compared to what we know today. For instance, in this 1885 map of the island of Singapore show above, Jurong is defined by the Pandan River to the south, West Bukit Timah to the north, Upper Tanglin to the east, and Peng Kang to the west. This illustrates how the geographical understanding and delineation of Jurong evolved over time. (Image Credit: Singapore Land Authority collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

In some of the earliest maps of Singapore island that were produced by the British during the early 19th century, "Jurong" was already being indicated. But what is the provenance of the name? Click or tap HERE to reveal below National Heritage Board's explanation in Jurong Heritage Trail (2015) (Call no.: RSING 915.95704 JUR).

"The roots of the name Jurong is more of a mystery however. It may derive from the Malay words jerung (a voracious shark), jurang (a gap or gorge) or penjuru (corner). The area between Sungei Jurong and Sungei Pandan was named Tanjong Penjuru (Cape Penjuru)." (p.3)

|

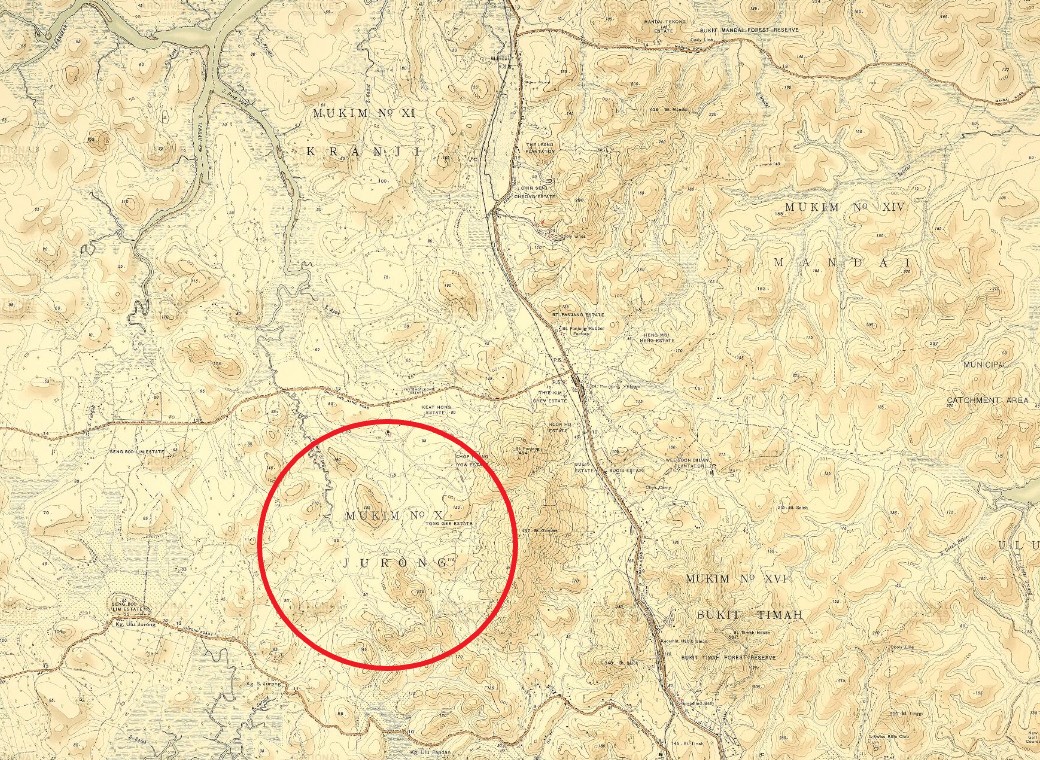

| Another way to define the boundaries of Jurong is by its Mukim or Town Division number. For instance, in the 1924 map above displaying the mukim numbers of various survey districts in Singapore, Jurong is marked with the mukim number “X” or “10”. Since the early 1900s, each land parcel in Singapore has been uniquely identified by a lot number, which consists of two parts: the survey district’s Mukim number and the lot number itself. Singapore is administratively divided into 34 Mukims and 30 Town Subdivisions, and this system helps in locating and organising land parcels within the country. (Image Credit: The National Archives (United Kingdom), courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

Before Jurong was developed into an industrial estate during the nation-building years, it was depicted in historical sources as an "undeveloped" region. However, what was it truly like during that era? Discover the first-hand account of Jurong in the 1930s from former Chief Surveyor Nagalingam Rameswaran in his 2000 oral history interview by clicking or tapping tap HERE. (Source: National Archives of Singapore)

"Jurong was a rubber state. There was no road inside, only Jurong road and Jurong was [a] very unrelenting country. Very hilly, valleys, then the river, and the river is swampy with mangrove, mangrove swamp, which I don't find now. And very few people or except those people working in the estate, rubber estate lived there. And the water there is well water, and some of them they have to take the muddy water and then filter it and take it. The boats, sampans were there in the river when they go to the sea to fishing and all. So, there was one Jew called David. He had a bungalow in the island at the opposite side. People go for a holiday with sampans. It is very underlain, no roads, nothing except rubber states, sometimes hills, valleys."

Peng Kang

During the 19th century, vast expanses of primary forest across the island, including the Jurong region, were cleared to make way for plantations, with a particular focus on gambier. The popularity of this cash crop was so significant that the areas encompassing today’s Jurong West and Boon Lay were once called ‘Peng Kang,’ a term derived from the practice of boiling gambier leaves.

|

| The name ‘Peng Kang’ (along with “Jurong”) can be seen on maps dating back to the 19th century. For instance, in this 1873 map of the island of Singapore, the regions of Peng Kang, along with Jurong, Pandan, and Tanjong Gul, are clearly indicated. Nested in the southwestern portion of the island, they vary in size, with Peng Kang appearing much larger than Jurong. (Image Credit: Singapore Land Authority collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| During the 19th century, significant portions of primary forests in Peng Kang, along with other parts of the island, were cleared for the establishment of plantations. In this 1855 map of Singapore Island, it shows that the cleared lands in Peng Kang and its surrounding areas, including Tengah (spelled ‘Tengeh’), Lim Chu Kang, Jurong, and Pandan, were mostly used to grow gambier and pepper. (Image Credit: Singapore Land Authority collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

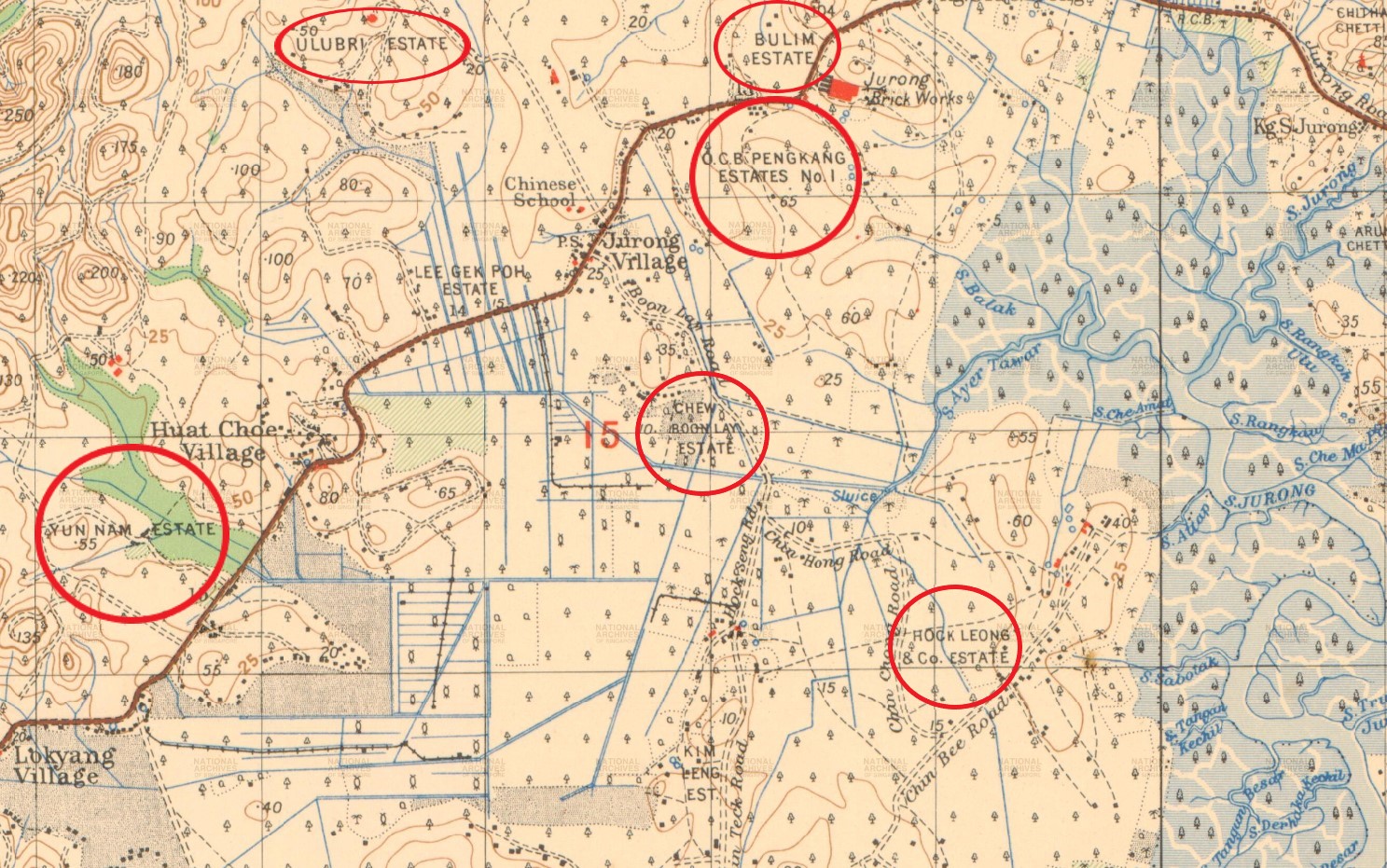

| The gambier industry saw a decline in the late 1800s. However, during the early 1900s, rubber, a new cash crop, gained prominence, largely due to global demand. This shift led to the replacement of gambier estates with rubber plantations, a change exemplified by influential entrepreneurs like Chew Boon Lay. In addition to his involvement in rubber, Chew had diverse business interests, including barter trading and the establishment of the Ho Ho Biscuit Factory in 1898. Chew passed away in 1933, but his legacy today is remembered through the naming of the housing estate of Boon Lay, as well as Boon Lay Road and Boon Lay Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) station. (Image Credit: Singapore Land Authority collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| While Peng Kang has been renamed Jurong West and Boon Lay, its historical presence can still be observed through the names Peng Kang Avenue and the upcoming Peng Kang Hill MRT station in the Jurong Regional Line. Additionally, Peng Kang’s survey district number, Mukim VI, assigned in the early 1900s, continues to be in use today by the Singapore Land Authority, preserving the historical connection of this area to its past name. (Image Credit: The National Archives (United Kingdom), courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

Gambier and pepper, pepper and gambier? Do you know why this two cash crops were always mentioned together in history books? Click or tap HERE to reveal Senior Librarian Timothy Pwee's explanation in his Biblioasia article, "From Gambier to Pepper: Plantation Agriculture in Singapore".

"Commonly grown alongside gambier is pepper. Although pepper was a much more profitable crop, the plant takes three years before it can be harvested. Additionally, the pepper plant is a vine that requires frames for support to grow upwards and also needs to be fertilised regularly. The boiled gambier leaves provide much-needed fertiliser for pepper plants which is why the two crops are often grown together; gambier would be planted while waiting for the pepper vines to start bearing fruits."

Communities of Early Jurong

The deforestation of Jurong and its adjacent areas like Peng Kang attracted new settlers to the region. The majority of these settlers were Chinese, and over time, they established villages in the area. They joined the existing local Malay and Orang Laut communities, who had been residing there, particularly along the coastal areas, even before the arrival of the British.

|

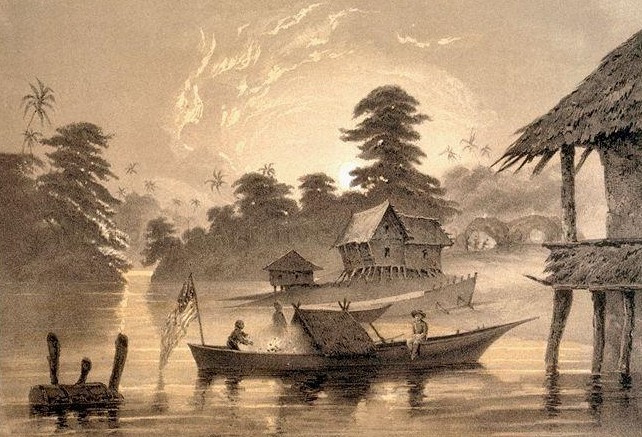

| The Orang Laut were sea and river-based nomadic communities who had been living in Singapore and the surrounding region since at least the 16th century. The British documented some of their tribes or sukus after their arrival, including Orang Biduanda Kallang, Orang Galang, Orang Gelam, Orang Seletar, Orang Selat, and Orang Sembulun. The Orang Sembulun were likely situated in Pulau Samulun, an island off the coast of Jurong at the end of the Jurong River. The image above, a lithograph, shows a canoe with an American flag on its stern approaching huts along the Jurong River bank. It was created by Peter Bernhard Wilhelm Heine, who was part of Commodore Matthew Perry’s 1854 expedition to Japan. (Image Credit: Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

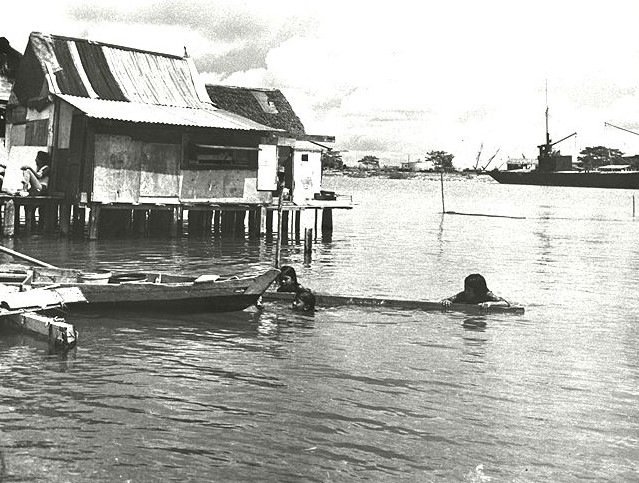

| In addition to the Orang Laut, the local Malay communities had long been residing along the Jurong River and the coastal areas of Jurong. Although they had distinct cultural backgrounds, the Malays and the Orang Laut shared a mutually beneficial relationship, often serving as the naval forces for various Malay kingdoms. Both communities relied on the resources of the land and sea, engaging in subsistence fishing, collecting plants and fruits from the forest for sustenance and medicinal purposes, and utilizing freshwater streams. The image above is a photograph from the 1950s depicting a fishing village along the Jurong River, illustrating the historical significance of these activities in the region. (Image Credit: Han Chou Yuan Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| The arrival of the British in 1819 led to the influx of new settlers in the Jurong area, primarily from China. These settlers, mainly from the Ann Kway Hokkien community in Anxi county, Fujian Province, took on the challenging task of clearing forests and swamps for the establishment of pepper and gambier plantations, where they later worked as laborers. They were eventually joined by Teochew migrants from Jieyang Province. Both the Hokkiens and Teochews established villages, or kampongs, in the area, with many of these kampongs situated between the 7th and 18th milestone along Jurong Road, one of the oldest roads in western Singapore. An example of such a kampong is Hong Kah Village, captured in the photograph from 1986. Established in the early 1800s, it was originally located at the 12th milestone of Jurong Road. Its name, derived from the Hokkien and Teochew term for “bestowing a religion,” also referred to Chinese Christians at the time. (Image Credit: Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

When villages like Ama Keng were established, schools played a pivotal role as essential structures to ensure that the children in these communities had access to education. Situated in rural areas, these schools differed significantly from those in the town centre such as Raffles Institution and St. Joseph, both in terms of size and structure. But in what specific ways were they distinct? Former Deputy General Secretary of NTUC, Lawrence Sia, sheds light on these differences in his 2007 oral history interview. Click or tap HERE to read what he shared. (Source: National Archives of Singapore)

"Now Ama Keng in Jurong, let me explain. It’s a new generation of schools at that point in time. You see, pre-war days they would have built schools like Raffles Institution, Victoria School, Rangoon Road School, Telok Kurau Primary School and Serangoon English School. Of course, St. Joseph's Institution, St. Andrew's - some of these schools were built pre-war, I mean, the structure. But then, you see, at that point of time there were very, very small population of people who went to these schools. So those schools were enough. Then after the war, when the war ended in 1946, the British came back, started to rebuild the administration…[But] they could not build the schools like how they built before because those schools were very expensive to build…They [also] could not build because they want to expand fast, they want to cater for a growing number of people….And so the schools had to be very simple but suitable. They are usually [on] a big piece of land with a field and it's a one-storey building. Not even two-storey initially. In Jurong and Ama Keng, they were one-storey only. Ama Keng was near the Tengah Air Field; one-storey...That's how I went there but very nice; airy, in the open air, no HDB flats around that's for certain, plenty of land.”

|

| In the early 1900s, the growth of existing and new villages in rural areas like Jurong was driven by various factors, including the expansion of rubber plantations, the establishment of British military bases, and improvements to the road and transportation network. By the late 1950s, many of these rural villages were well-equipped with basic amenities and services, such as schools, places of worship, markets, provision shops, and even clinics. The image above shows Sin Nan Public School, founded in 1932 near Hong Kah Village. Today, the school is situated in Jurong West and is known as Xingnan Primary School. (Image Credit: Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

Still trying to envision how Jurong appeared during its early days before industrialisation? Architect Philip Conn, who spearheaded the restoration project of Fort Canning Bunker (now The Battlebox) in 1996, offers a vivid account in his 2013 oral history interview. Click or tap HERE to find out what he shared including his advice against jogging through the rustic countryside. (Source: National Archives of Singapore)

"Well, I had a nose for seeking these things out. I would drive up all the back streets and the tracks. Running on the hash, we used to find these places too, we'd go into all the old kampong areas and in the old days, on the hash, there were still kampongs and swamp areas in Jurong and that was when it was interesting. A number of fish ponds I've fallen into and what they call shiggy pitts, which are the sort of sewerage pits from pit farms that I've almost fallen into! The terrible things about those things is they are hole in the ground, and they drain, in a little kampong, you have a house with half of those pigs in the back, and the drain will go into this deep hole about two metres deep, and about metre and a half square, and when it fills up with water, you get this film on the top, looks a bit like, not like a beer, it's sort of brownish and white and smooth like someone has thrown some concrete down and just let it sit there, so when you're running along a rotten path in the jungle, you see when you tend to run in just for a couple of paces, because it looks like a piece of concrete on the ground, but then you go up to your neck and, "ping" whatever. That's happened to a few friends of mine! All that's gone by now, of course even the fish farms gone as well, but they were down there…”

Impact on the Landscape of Jurong

The early economic activities in the Jurong region had a lasting impact on the landscape there. When the British arrived in 1819, the region was covered in thick primary forests. But by the late 1870s, most of the forests had been cleared to make way for plantations.

|

| The vast forests in Jurong and other parts of Singapore were cleared to make room for plantations, particularly for crops like gambier and pepper. Chinese farmers began large-scale cultivation of these crops in the 1830s. They settled in remote river areas in Singapore and initiated the planting of gambier and pepper. They employed a practice known as shifting cultivation, which involved clearing the primary forests to grow their crops. After roughly 15 years, when the soil’s fertility declined and local timber and firewood resources were exhausted, they would relocate to new, untouched land to continue their farming. The 1900s photograph above portrays a scene of a Gambier and pepper plantation. (Image Credit: Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board) |

|

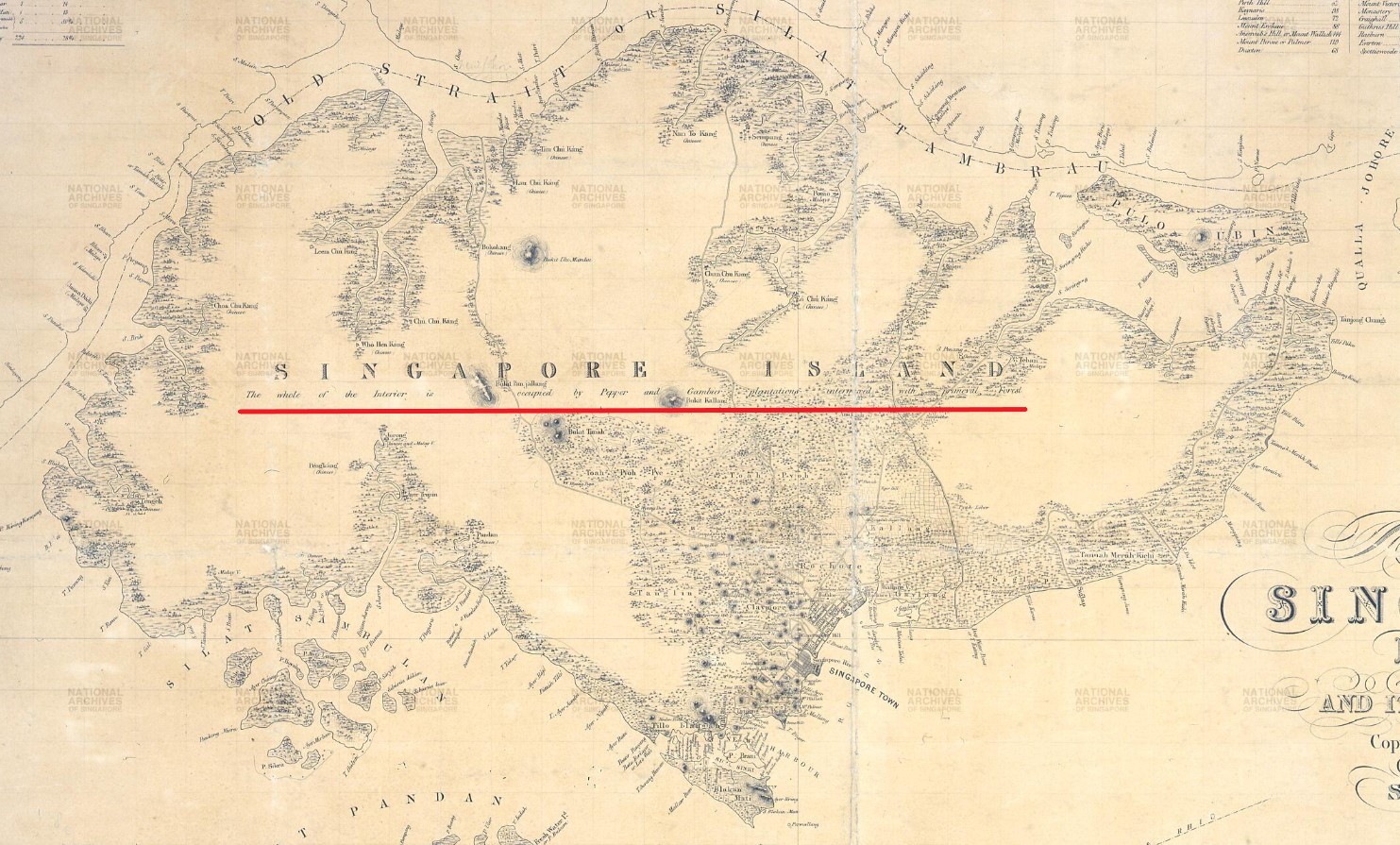

| The expansion of gambier plantations in Singapore can be attributed to several factors such as relocating the gambier market from Riau to Singapore and eliminating trade taxes on gambier. By the late 1840s, a significant portion of the primary forests in Singapore had been cleared haphazardly, resulting in the setting up of approximately 400 gambier and pepper plantations across the island. By 1855, Singapore boasted an estimated 12.5 million gambier trees and 1.5 million pepper vines distributed across over 540 documented plantations. The rapid growth of gambier and pepper plantations across the island can be seen in the above 1852 map of Singapore island as its interior was described, “The whole of the Interior is occupied by Pepper and Gambier plantations interred with primeval Forest”. The National Archives (United Kingdom), courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

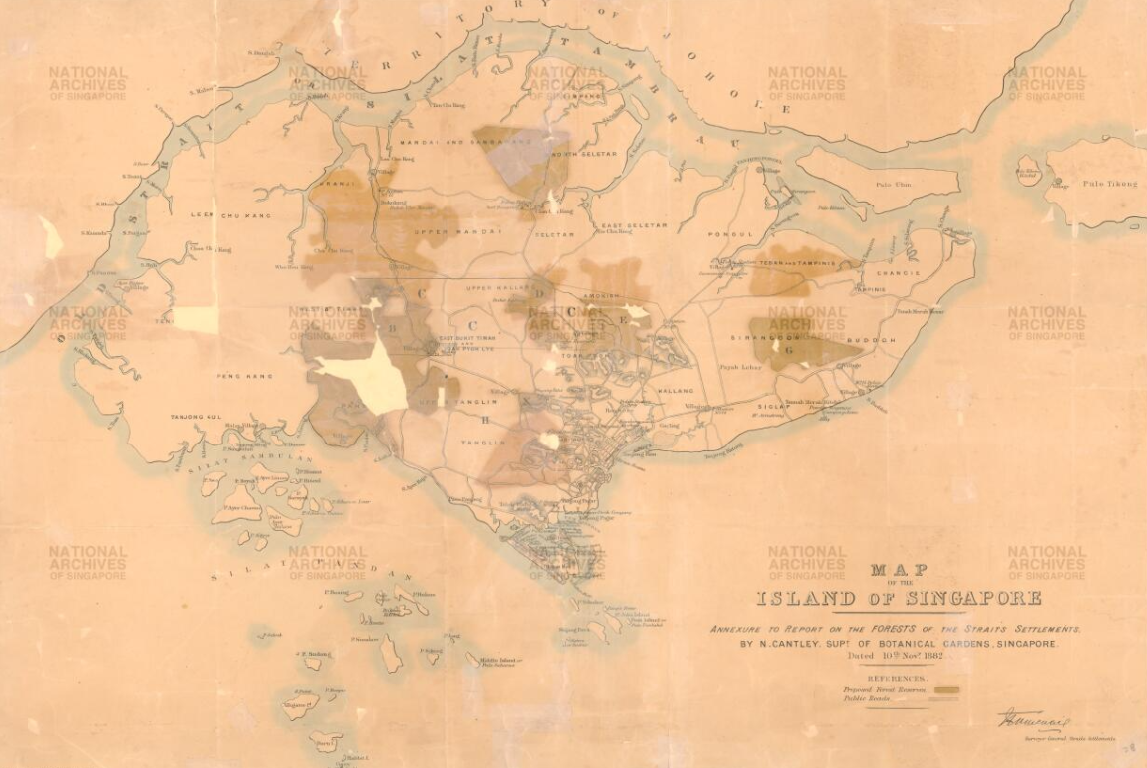

|

| Deforestation in Singapore continued without any controls until the late 1870s. It was only in 1879 that the colonial government, through John F.A. McNair, assessed the condition of timber forests in the Straits Settlements. McNair’s report in 1879 described a dire situation in Singapore, with diminishing timber resources, unregulated deforestation, and a lack of forest protection laws. Despite this alarming report, no immediate action was taken to protect the forests. It wasn’t until 1883 when Governor Frederick A. Weld commissioned another report by Nathaniel Cantley, the Superintendent of the Botanic Gardens. Cantley’s report reiterated the extensive deforestation in Singapore and the absence of conservation efforts. Finally, the government acted on Cantley’s recommendations, leading to the establishment of 12 forest reserves covering approximately 8,000 acres in 1886. Some of these reserves, including Jurong, Pandan, Kranji, and Chan Chu Kang, were situated in Jurong and the western region. These reserves were managed by a Forestry Department within the Botanic Gardens. The map above shows the location of the forest reserves (shaded) that Cantley proposed in his 1883 report. (Image Credit: Singapore Land Authority collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| Generations of human activities on the island, particularly in the Jurong region, had detrimental effects on the local wildlife. Deforestation, hunting for both sport and sustenance, and the illegal animal trade in Singapore resulted in the decline of various animal species, including tigers. In the first half of the 19th century, the expansion of gambier and pepper plantations increased encounters with tigers because these animals lost their natural prey and the shelter of thick forests. To address this issue, the government started offering rewards for the hunting of tigers. Although this significantly reduced the sighthings of tigers, it eventually led to their eradication in Singapore. The last wild tiger that was hunted down in Singapore took place in 1930 near Choa Chu Kang Village. Shown above is an 1890 photograph of a hunter posing with a dead tiger. (Image Credit: Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

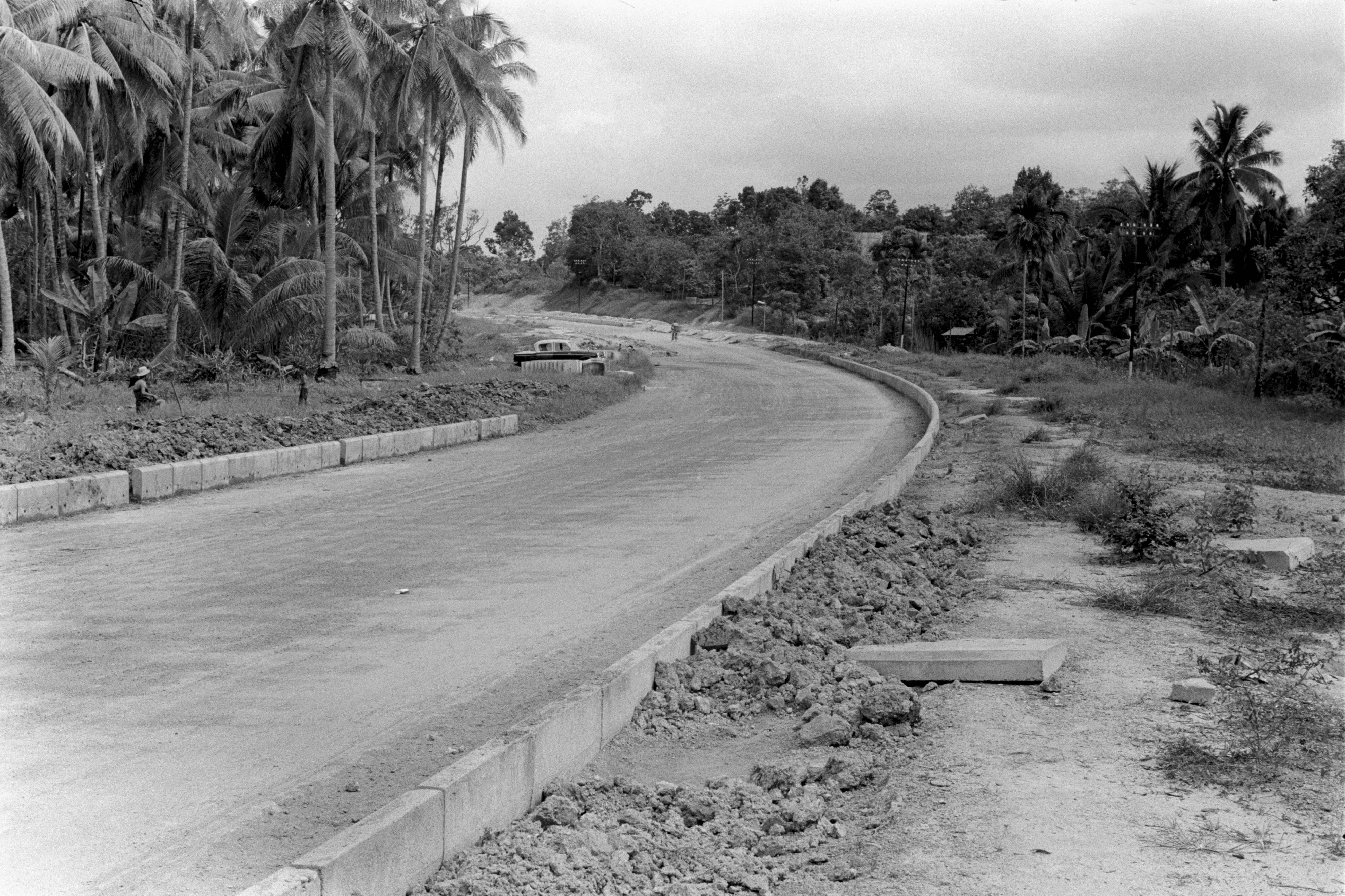

|

| The landscape of Jurong was further impacted by the construction of roads and the establishment of small villages with farms. These changes not only improved accessibility to the region but also resulted in the conversion of once undeveloped land into areas for agriculture and residences, playing a crucial role in altering the landscape of Jurong. Shown above is a 1962 photograph of Jurong Link Road being constructed. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

Choa Chu Kang, Lim Chu Kang and Phua Chu Kang. Ever wondered why there are So many "Chu Kangs" in Singapore? Except for the fictional local sitcom character, "Phua Chu Kang", there is a story behind why Choa Chu Kang and Lim Chu Kang were named this way. Click or tap HERE to find out below. (Source: "Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society [Vol. 49, No. 2 (230) (1976)]").

The Chinese plantations were organised under a system led by a headman known as a "kangchu," which translates to "lord of the river" in Teochew. The kangchu oversaw the transformation of virgin jungle areas near river catchments into plantations. These areas were also referred to as "bangsals" (“shed” or “lean-to shelter” in Malay) in reference to the cultivated zones where gambier and pepper were grown as well as the processing facilities and accommodations for the workers within. Typically covering an area of 10 to 50 acres, each bangsal usually employed around 10 workers. These bangsals were situated along major rivers, including the Jurong River, and the settlements of each plantation cluster were known as "Kangkar", which means "foot of the river" in Teochew.

References

Click the following PDF icon to view and download the reference list used for this page: