Industrial Revolution

Littered with villages, plantations, swamplands and patches of primary forests, Jurong was largely undeveloped until then-Finance Minister Dr Goh Keng Swee mooted the idea in the early 1960s of turning Jurong into the 9,000-acre industrial estate to spearhead Singapore’s industrialisation plans. Despite being a risky plan given that Singapore had little experience in creating an industrial town of this size, the government pressed ahead. In less than a decade, Jurong was transformed into a hub of factories and industrial activities.

Early Economic Activities in Jurong

Before the development of the Jurong Industrial Estate, there were already some economic activities in the area involving plantations and farms. These not only brought settlers to the area, but also led to the clearing of forests to create lands for the establishment of estates and farms.

|

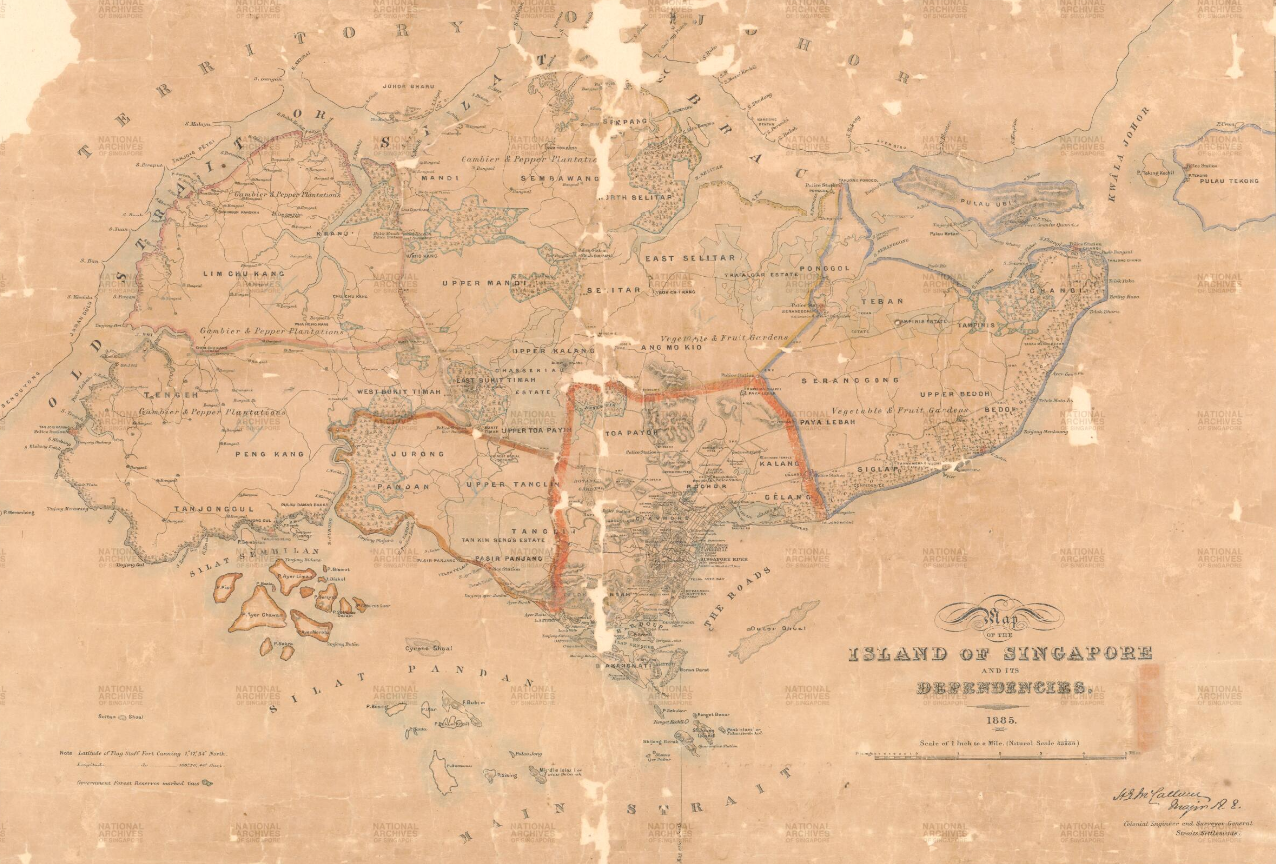

| After the British arrived in 1819, a significant portion of land on Singapore island was used for growing commercial crops, with the most important ones being pepper, gambier, nutmeg, coconut, pineapple, and rubber. In places like Jurong and others in the western part of the island, including Peng Kang, Choa Chu Kang, and Bukit Timah, the landscape was initially covered with primary forests. However, they were cleared to make way for gambier and pepper plantations for most of the 19th century. These plantations were later replaced by rubber and pineapple estates in the early 20th century. The prevalence of gambier and pepper plantations in the western and northern parts of Singapore during the 19th century is evident in the 1885 Map of The Island of Singapore and Its Dependencies shown above. (Image Credit: Singapore Land Authority collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| In contrast to many other parts of Asia where European landowners dominated estate agriculture during that period, most of the rubber plantations in Singapore and Johor were owned by local individuals. Prominent local business leaders who owned rubber estates in Jurong included Chew Boon Lay and Tan Lark Sye. The Sembawang Rubber Plantations Limited company, which was formed by Lim Boon Keng, Tan Chay Yan, and Lee Choon Guan, also had holdings in the area. Members of the Chettiar community owned estates here, such as Chithambaram Chettiar Estate and Arunachalam Chettiar Estate near Kampong Sungei Jurong. Additionally, there were other rubber holdings in Jurong like the Bajau, Jurong, Lokyang, Yun Nam, Chong Keng, Seng Toh, and Lee Gek Poh estates. Some of these estates including Chew Boon Lay’s are indicated in this 1945 map of Singapore. (Image Credit: Singapore Land Authority collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

Boon Lay derived its name from Chew Boon Lay, a significant figure among Singapore's early pioneers. Chew He once owned extensive tracts of land in Jurong where he grew pepper and gambier, and later rubber. Additionally, he also founded the Ho Ho Biscuit Factory. Curious about how Chew managed his business empire? Find out by clicking or tapping HERE to read an account taken from his grandson, pioneer architect Victor Chew of Kumpulan Akitek's 1997 oral history interview. (Source: National Archives of Singapore)

"[A] lot of these other well-known people were like Nee Soon and all that, names like that, they're all very rich people but they own a lot of, basically they are just rubber estates owners and that's that. Whereas my grandfather he had many rubber estates…[I]n those days, if you look after the estate, you live there, you create a family there, you had your own tiny village there so that was one son. Another son would be in another estate. My eldest uncle, I think, and eighth uncle looked after Jurong and they, the two brothers also look after the biscuits Ho Ho [Biscuit Factory] site and there's another one look after another estate, that was the Chinese way of doing [things]. You don't have branch managers. You have your sons, you set up your sons in each one in his own little environment then you done your job as the patriarch of the family…[F]actory like Ho Ho Biscuit Factory…[could be one of the] very few factories that as I said, made biscuits and sweets and soap, things like that….[I]n that respect ironically, I see him as one of the pioneers of industry here, that's the way I see him. Ironically, his estate in Jurong is now the Jurong Industrial Estate. I suppose he wouldn't have minded it too much if he knew that it was going to be such a successful industrial estate. He was always very, very, one of the early people, one of the early pioneers, who had great faith in manufacturing…”

|

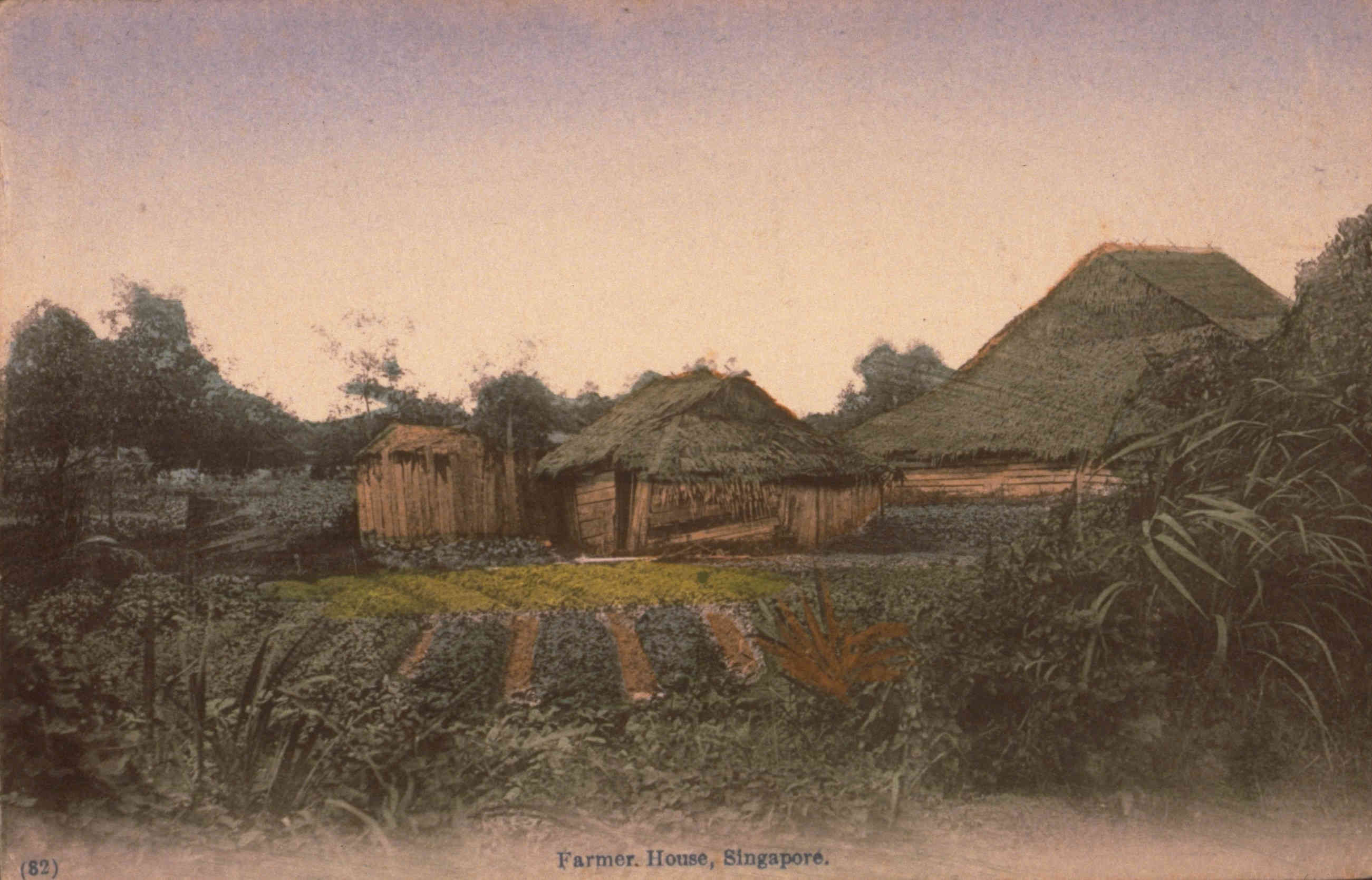

| In the early 1900s, Jurong and its nearby areas emerged as a crucial hub for agricultural production in Singapore. This was due to several reasons, including the growth of vegetable and fruit farms that took over the land previously used by abandoned plantations and disappearing patches of forest. This development was influenced by factors such as improved road networks into rural areas, the redevelopment of farmlands on the town’s outskirts for various purposes, and an increasing demand for fresh vegetables, fruits, pork, and poultry due to the growing population. Shown above is an early 20th century postcard showing a small plot of vegetable farm in a rural village in Singapore. (Image Credit: Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| Fishing and prawn farming were also prevalent along the rivers and coastline of Jurong. These practices had long been associated with the Orang Laut (sea nomads) and Malay settlers in the area, and in the 1900s, fishing farms and prawn ponds experienced substantial growth. Carp farms, known for their high yield, were a popular source of food in Singapore before the war. Additionally, prawn ponds in the muddy river estuaries and mangrove swamps of Jurong were among the largest and most productive on the island. In the 1950s, they covered about 1,000 acres of land and yielded up to 1,000 kilograms of prawns per acre. Shown above is a 1955 photograph of a man casting a net to catch prawns in Singapore. (Image Credit: Donald Moore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

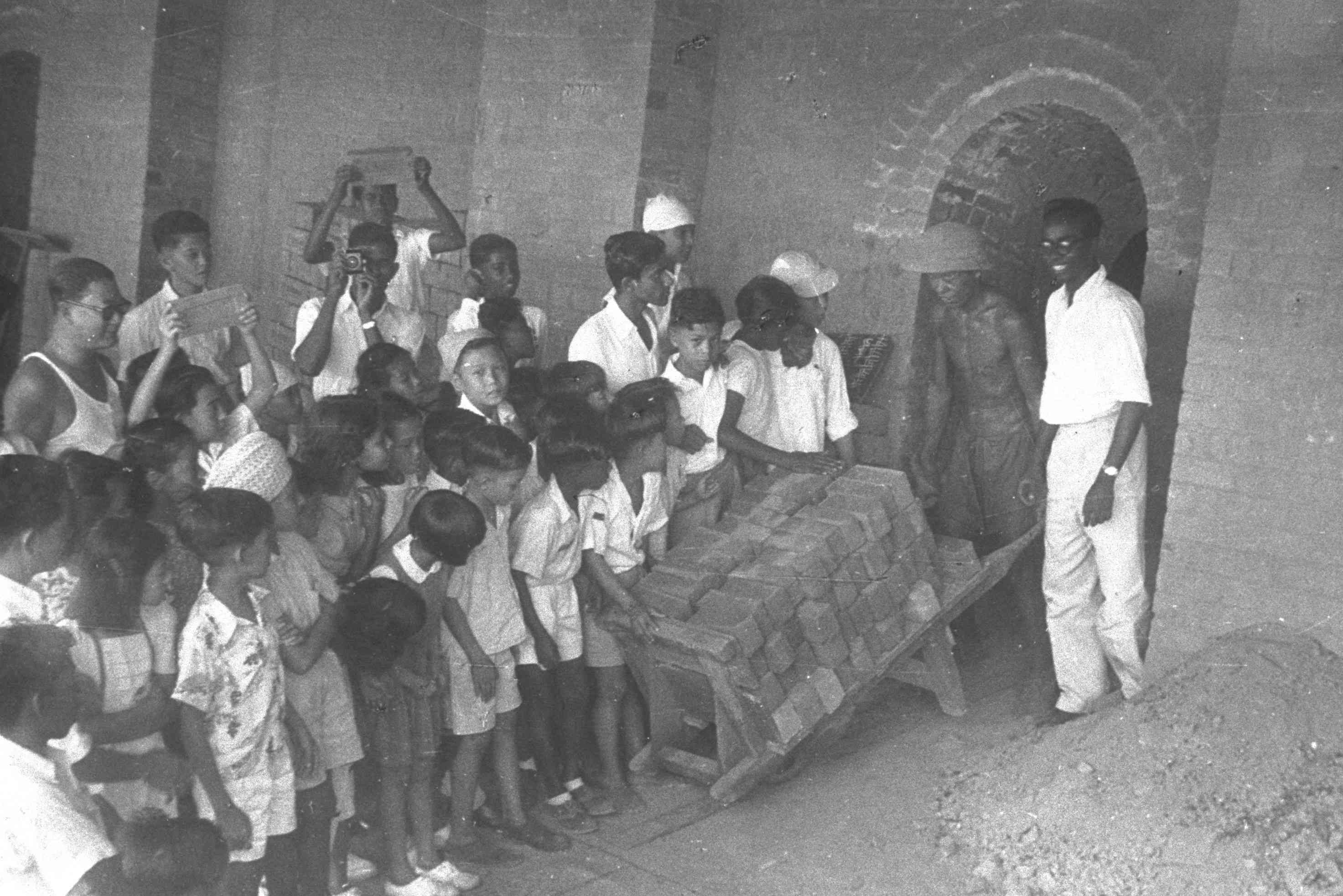

| While early Jurong was primarily known for its agriculture, several industrial ventures were also established. Starting from the 1920s, the area was home to a number of brickworks that employed somewhat basic techniques. These brickworks used cows or buffaloes to tread on the earth, turning it into a sticky paste. Workers would then shape the bricks by hand before baking them in brick kilns. Before World War II, some of the brickworks in Jurong began using machines in the brick-making process, significantly increasing production. During the 1970s, the area saw the operation of several prominent brick makers, including Jurong Brick Works and Ba Gua (Eight Diagrams) Kiln. Above is a photograph from 1952 capturing a group of students observing the process of removing bricks from a kiln. (Image Credit: Bukit Panjang Government School Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

Why do Chinese plantation owners choose to cultivate rubber and pineapples on the same plot of land? What benefits or synergies do they find in this unique combination of crops? Click or tap HERE to find out below National Heritage Board's explanation in the Jurong Heritage Trail (2015) (Call no.: RSING 915.95704 JUR).

"Unlike estate agriculture elsewhere in Asia at the time, which was largely dominated by Europeans, almost all of the rubber plantations in Singapore and Johor were owned by locals. The Chinese often planted interim cash crops such as pineapple or gambier among the rows of rubber trees, and these crops that yielded their produce within 18 months generated cash flow while the rubber trees matured. With the revenue from these interim crops, and smaller capital investments in their rubber plantations than that of their European counterparts, it cost Chinese planters around 150 Straits dollars per acre of their rubber estate. This was in contrast to European estates that could require up to four times the capital investment. (p. 14)"

Building an Industrial Estate

Although early economic activities had already transformed parts of the Jurong region, particularly along the coastal area, some areas, including swamplands, remained largely undeveloped. However, this landscape was destined to change in the early 1960s when Jurong was officially designated as Singapore’s first industrial estate.

|

| The development of Jurong as Singapore’s first industrial estate commenced in 1961. Under the leadership of then Finance Minister Goh Keng Swee and Dutch economist Albert Winsemius, the industrialization project aimed to stimulate employment and economic growth. A 69-square-kilometer area in Jurong was designated for industrial development. To realize this vision, the landscape underwent significant changes, with low hills being flattened, and swampy areas reclaimed to prepare the land for various industrial, infrastructural, residential, and recreational purposes. The photograph above, taken in 1962, captures the early stages of the Jurong Industrial Estate’s development. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| The Jurong Industrial Estate project commenced with the laying of the foundation stone for the National Iron & Steel Mills, now known as NatSteel, on 1 September 1962. Throughout its development, the estate accommodated various industries, including timber, sawmilling, oil-rig fabrication, shipbuilding, and repair. By 1976, the estate boasted 650 factories, with more than 20,000 flats occupied, indicating a substantial expansion of industrial and residential activities in the area. The photograph above, taken in 1963, showcases NatSteel’s plant in Jurong. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

National Iron & Steel Mills (today’s NatSteel) located at 17 Tanjong Kling Road was the first factory to be built in Jurong Industrial Estate. Set up in 1961, it started by supplying steel to Singapore’s construction industry before beginning to export its steel products in the 1970s as it expanded. Click or tap HERE to find out from one of the company’s founding members Tan I Tong on how the company chose its factory site and later started operations in his 1999 oral history interview. (Source: National Archives of Singapore)

"It's a piece of flat land [with] a lot of tractors working. I think you had to trust the EDB. You know it's the government. They said you can go [there] and choose [a site]. So we chose after discussion with Goh Seong Pek, I said we should choose the seaside. He went to see….In 1961, [there were] still some prawn ponds, some hills [at the site].

The NatSteel site is on the hill of about 60 feet, [but later] cut into flat [land]. And then we did not need piling….[As] it is industrial estate, what we are concerned is only whether we can see the steel done. There's water, there's electricity. Then next one is can you get workers, get the market, selling price and so on….

[The Government] planned the whole industrial estate. We only planned our steel mill. Then we employed [new workers]. [Since] we got a small...we could only employ one American consultant who was in steel. Anyway, he was Kansas Steel America. Then we were able to employ one British smelter working in the steel mill workshop. He got a roller - English roller who roll the millet or ingot into steel bars…Then Goh Seong Pek was able to get 16, I think, technicians from Taiwan and four engineers, technicians from Taiwan. Then with Hon Sui Sen recommendations, we took the poly graduates, seven…These were the production department, [and] how we started…But you are learning from the Taiwan technicians - melting, rolling, electrical, mechanical, maintenance, everything... And they were here about five years…[And] one of the conditions you must train our local technicians in [these] five years. Within the five years, you had to train them [in] steel mill operation…

And what about those people like yourself, the top bosses yourself? Before that, you know nothing about steel business, how did you actually learn the trade yourself? That one, we learnt only after we joined. Half working, half study - half working, half study.”

|

| The development and administration of the Jurong Industrial Estate were initially overseen by the Economic Development Board (EDB). Established in 1961, the EDB played a pivotal role in encouraging foreign companies to establish factories in Jurong by offering industrial financing and incentive packages. By 1967, marking the completion of the first phase of development, the Jurong Industrial Estate had successfully attracted investments totaling approximately S$178 million in fixed assets and had generated employment opportunities for around 6,500 workers. The aerial photograph above, taken in 1960, provides a view of the Jurong Industrial Estate. (Image Credit: David Ng Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| As Singapore intensified its industrialisation efforts after gaining independence on August 9, 1965, the government recognized the increasing complexity of managing industrial estates. Consequently, the decision was made to transfer this responsibility from the Economic Development Board (EDB) to the newly established Jurong Town Corporation (currently known as JTC Corporation or JTC). Alongside managing and expanding Singapore’s industrial estates, JTC was tasked with providing amenities to enhance the quality of life for those working and residing within these estates. The photograph above, taken in 1975, shows Jurong Town Hall, which served as the headquarters of the Jurong Town Corporation. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

The transformation of Jurong into an industrial estate was one of the nation-building success stories of Singapore. But how and why this project was initiated in the first place? Click or tap HERE for former Director of Public Works Department Dr Hiew Siew Nam’s account taken from his 1993 oral history interview. (Source: National Archives of Singapore)

"[T]he new PAP Government has invited a UNDP committee to come and advise us about economic development, particularly in Jurong where a big area is covered by swamps. The UNDP team produced a report and submitted to Minister for Finance.

In fact, all these were prompted and initiated by Dr Goh [Keng Swee]. His whole idea of the new Government is that we must embark on economic development in order to alleviate two very important strategies. One is that we are no more going to depend purely on trade or as a trading city. We have to embark on our own economic development rather than purely on trade. Secondly, being a small country, we have to make good use of whatever land that we have so as to turn it into productive enterprises.

So the UNDP committee came and submitted a report of how to turn Jurong, hitherto a swamp, into an industrial estate. The report was submitted to Government. Dr Goh has appointed Mr Hon Sui Sen (at that time he's Head of EDB) to form a committee to look into the feasibility of this report.

Well, the early problem of JTC is to fill up all the swamps into land capable of sustaining the building works. That's the main task of JTC during the early years. It's purely reclamation and filling up the swamps and turning it [for] land use. After that, then JTC started building standard factory buildings and invited local entrepreneurs to start their industry in Singapore. I think the early problem is purely providing infrastructures for all the interested companies to set up there.

I think the EDB has done a very good job in promoting this industrial estate to all the local entrepreneurs and multi-national firms. I think they managed to get most of these people interested. The Corporation, I think, started very well when all these enterprises and industries were ensured that their enterprises will receive Government assistance. Various incentives were given to them to start their work. For one thing, their starting capital expenditure will be very much less. They have got ready infrastructures for their enterprise. They have got a ready factory to start their work. So as far as capital cost is concerned, that helps them to start their business with the least capital expenses. And they are ensured of all sorts of incentives given by the EDB to establish their industries in Jurong. I think the public has very good response to these Government-promoted projects.”

Building Industries

The types of industries that could be found in the Jurong Industrial Estate evolved in tandem with Singapore’s industrial development strategy. In general, the strategy underwent five phrases of evolution, starting from labor intensive in the 1960s, followed by skill intensive in the 1970s, capital intensive in the 1980s, technology intensive in the 1990s, and knowledge and innovation intensive from the 2000s onward. Some of the key industries that emerged during this process included manufacturing, electronics, shipbuilding, petrochemicals, and biomedical sciences.

|

| In the 1960s, Singapore faced high unemployment and began focusing on creating jobs and boosting its economy through labour-intensive industrialisation. This gave rise to the development of the country’s manufacturing sector and the setting up of factories in Jurong to produce goods like clothes, toys, and more. This was a significant shift for Singapore, which had relied on trading since the British established it in 1819. The government, particularly the Economic Development Board (EDB) and Jurong Town Corporation, played essential roles in planning and managing this industrialisation process. By the mid-1970s, manufacturing had become a significant part of the economy, and Singapore actively sought foreign investors to compensate for its limited domestic resources and market. Shown above is a 1964 photograph of the Pelican Textiles Factory in Jurong. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| As part of the overall economic strategy in the 1960s, shipbuilding and repair industry were also identified as one of the essential components of the country’s industrialisation process. To take advantage of the newly established Jurong Industrial Estate and Jurong Port in the early 1960s, the government established Jurong Shipyard in April 1963. This new facility was tasked with constructing, maintaining, and repairing various types of ships and vessels. Following the formation of Jurong Shipyard, the government also moved forward to develop shipyards at Keppel and Sembawang. Over the next 40 years, Singapore’s marine industry has grown from a small regional ship repair and building center into a global leader. This industry includes ship repair, shipbuilding, rig building, and offshore engineering, along with various supporting services. Singapore is now renowned as a top ship repair and conversion center, a leader in jack-up rig building, and a builder of custom and specialised vessels. Shown above is a photograph of Jurong Shipyard taken during the initiation ceremony of its drydock in 1968. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| Jurong is also the stage for the development of the country’s petrochemical industry. A game-changer was the creation of Jurong Island, achieved through a substantial investment in land reclamation, which has become the heart of Singapore’s petrochemical industry. This island cluster houses various petrochemical-related businesses, separates more polluting processes from the main island, and has attracted substantial investments and a large workforce. Emphasizing cluster development is a key economic theme. After the success of Jurong Island, Singapore launched the Jurong Island Version 2.0 initiative in 2010, focusing on research and optimization, including the development of the Jurong Rock Caverns, an underground liquid hydrocarbon storage facility. Above is a 1999 photograph showing the land reclamation works at Jurong Island. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

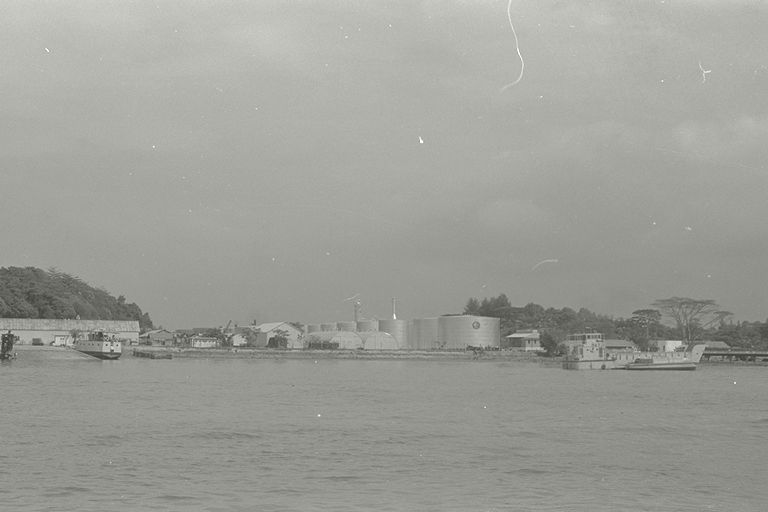

| Singapore’s connection with the oil and oil refining industry dates back to 1892 when Marcus Samuel and Company used Pulau Bukom as a storage center for kerosene. This island became a vital hub in the East, supplying the company’s other facilities. Shell, as it later became known, entered the refining business in 1961 and it redeveloped its storage centre on Pulau Bukom into a 20,000-barrels-per-day refinery. Shell’s commitment paved the way for other companies to follow suit turning Singapore is a major global center for oil refining. Above is a 1960 photograph showing the oil refinery at Pulau Bukom. (Image Credit: Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

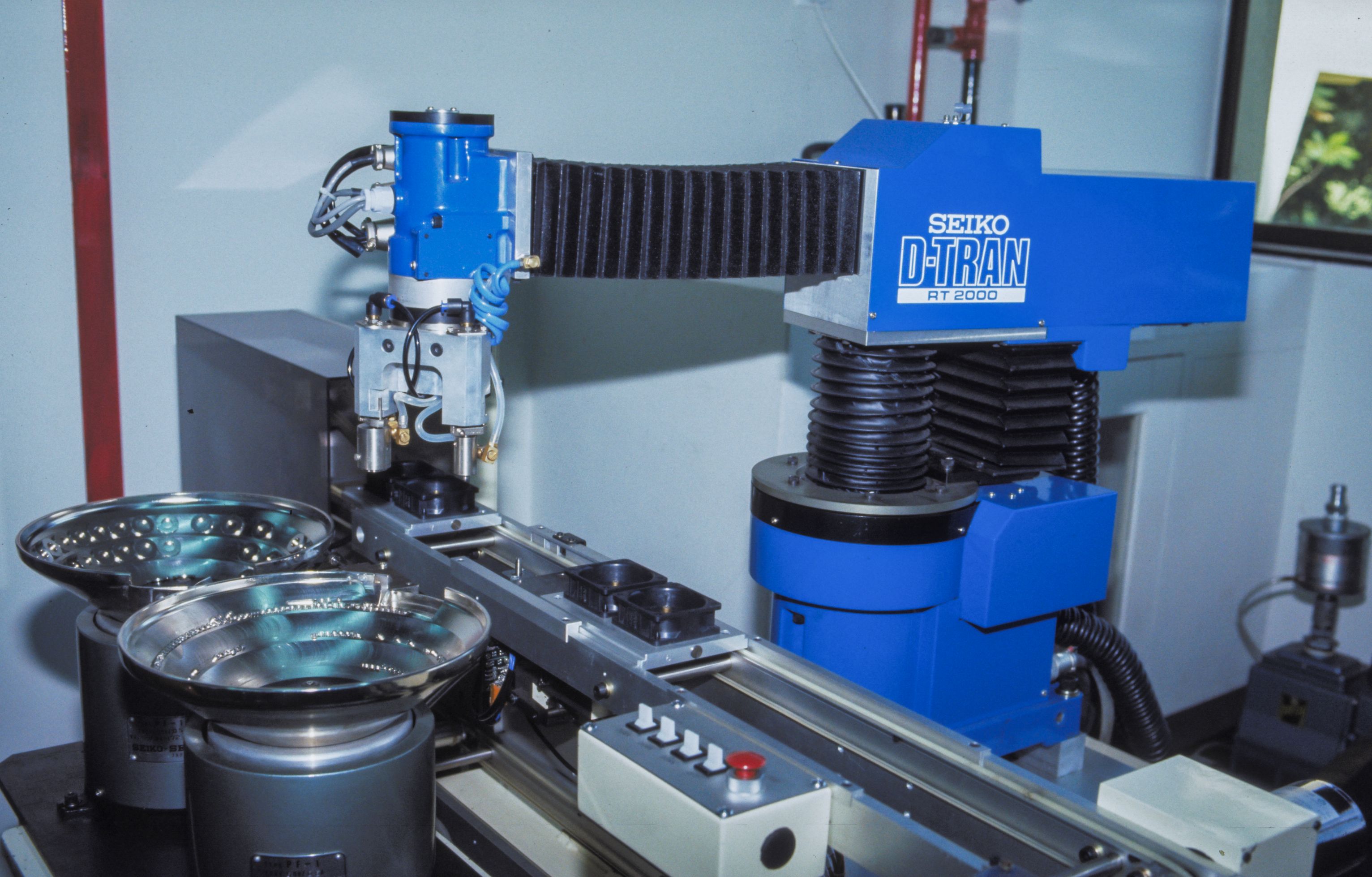

| As industrial development gained speed in the 1970s, the government of Singapore started to shift from low-cost, labor-intensive industries to higher-value, skilled jobs and businesses by developing technical and business expertise. They actively worked to attract foreign investment from Europe, North Asia, and the United States by positioning Singapore as a global business hub for companies. This led to substantial investments in the emerging industries in fields such as precision engineering and electronics for the production of precision products such as camera optics, tool-making and precision machineries, as well as high-tech products like computer parts and software. Many multinational companies, including Rollei, Aiwa, Texas Instruments and NEC, relocated or established research and development activities in Singapore. Above is a 1987 photograph showing the then Labour Minister Lee Yock Suan being briefed by an official during his tour of Aiwa’s manufacturing plant in Jurong. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| In the 1980s, Singapore continued to focus on diversifying its economy and transitioning its manufacturing sector to be more capital-intensive. Simultaneously, it started to position itself as a global business hub to attract international service corporations in finance, education, lifestyle, medicine, information technology, and software. In the 1990s, Singapore continued to diversify and advance its economy, with the introduction of the Strategic Economic Plan. This plan aimed to transform Singapore into a first-tier developed country by turning it into a knowledge-based and innovation-driven nation. To achieve this, a number of initiatives were taken. These included the establishment of the Science Park beside the National University of Singapore and the formation of the National Science and Technology Board. Later renamed A*STAR, this agency was tasked to focus on conducting, funding and attracting experts to drive research and development activities, as well as to conduct and support human capital training. Shown above is 1985 photograph of a mechanical robot at the Automation Applications Centre of Robot Leasing and Consultancy Pte Ltd in Science Park. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| From the 2000s, Singapore initiated the development of its biomedical science industry with the aim to turn it into a key economic pillar. A focus of this initiative centered on development of pharmaceuticals and medical technology and products. To aid this process, the Tuas Biomedical Park was established and it served as a node to attract major international pharmaceutical companies. In additional, publicly funded research institutes were also established to enhance capabilities in fields related to the biomedical industry. Similarly, financial support was also given tto promote industry research and startups in related areas such as pharmaceuticals, medical technology, healthcare services, and biotechnology. Shown here is the exterior of JTC’s Tuas Biomedical Park building at Tuas South Avenue 3.(Image Credit: Courtesy of Jurong Town Corporation) |

The formidable endeavour of establishing an industrial estate from the ground up in Jurong was not without its share of problems and challenges. Click or tap HERE to discover, from veteran civil servant and former chairman of Singapore Airlines, J. Y. Pillay, what some of these issues and challenges were in his 1995 oral history interview. (Source: National Archives of Singapore)

"Yes. There was the problem with squatters from time to time. It has to be expected. And some technical problems. I think there was a major disaster we suffered at the Jurong wharf where there was an earth slip at the wharf face, which cost us a lot of money to put right. I vaguely recall that the cost of that wharf was $40 million. Today it may not sound very much, but in those days $40 million was a colossal sum of money. The Economic Development Board started with $100 million, its capital spread over five years, $20 million each year. The $40 million was a lot of money. And I think this earth slip set us back $10 million to $15 million. That was a major technical problem.

At that stage it was crucial. The Government had to give a lead to set up the Economic Development Board to start with; established the Jurong industrial estate which was in the beginning under the EDB, to provide finance to companies to do the promotion. Those were all critical areas that accelerated the development process.

But I think we should also remind ourselves what were the fundamentals in terms of political and social stability and macro-economic stability. In other words, balanced budgets and a strong currency and so on. But we didn't, of course, start with political and social stability in the early sixties. There was still a good bit of industrial strife and a good bit of political struggle in Parliament and outside Parliament. But we did maintain macro-economic stability. That must have been crucial. We didn't spend beyond our means and we retained the internal and external value of the Singapore dollar, particularly the internal value. Inflation was very low.”

Building Infrastructure

The provision of infrastructure is integral to the development of any estate, whether it’s for commercial, housing, or industrial purposes, as it facilitates not only the movement of goods and workers but also the supply of electricity, water, and gas. Consequently, there was a boom in infrastructural works in Jurong as it was being developed into an industrial estate. These works included the construction of a port, a railway, a road network, and even a fishery port.

|

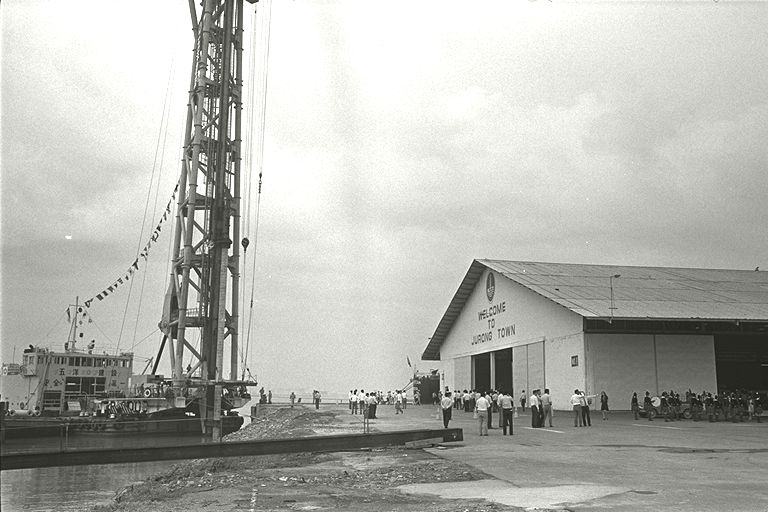

| Jurong Port started its operations in 1965. The natural deep waters in the vicinity of Jurong made it an ideal location for establishing the port. The first wharves were constructed in 1963, enabling the import of raw materials and the export of finished products from the factories in Jurong. The port handled a diverse range of cargo, including steel plates, industrial chemicals, timber, and even farm animals. Over the decades, it went through a series of improvement to expand its capabilities. Presently, the port boasts 32 berths, over 174,000 square meters of warehouse facilities, and can accommodate ships weighing up to 150,000 deadweight tonnes. Shown above is a 1975 photograph of Jurong Port. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

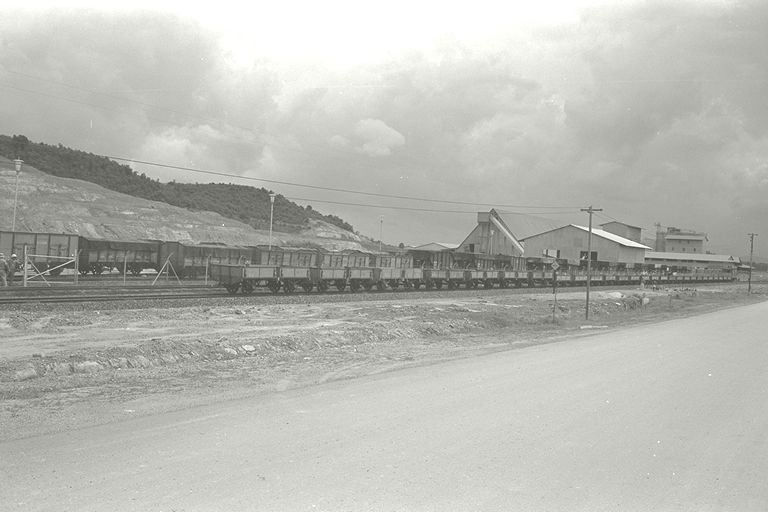

| The Jurong Railway, built in collaboration between the Economic Development Board (EDB) and Keretapi Tanah Melayu (KTM), also known as Malayan Railways Limited, served as a transportation route for clinker and timber, primarily from peninsular Malaysia into Jurong, while transporting manufactured products in the opposite direction. This railway operated as a spur line connected to the main Malaysia–Singapore railway, commencing from the Bukit Timah Railway Station near King Albert Park, passing through Pasir Panjang, and concluding at Shipyard Road close to the Mobil refinery. In the mid-1990s, the Jurong Railway was decommissioned due to changing logistics trends and the adoption of more efficient transportation methods. Shown above is a photograph of Jurong Railway taken in 1966. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| To capitalise on the newly established Jurong Industrial Estate and Jurong Port in the early 1960s, Jurong Shipyard was established in April 1963. This shipyard was tasked with the construction, maintenance, and repair of all types of ships and vessels. The establishment of Jurong Shipyard faced its share of challenges ranging from funding to obtaining the know-how. Despite these initial obstacles, the government, in collaboration with Japanese partners, set up the shipyard and went on to develop more at Keppel and Sembawang, thereby enhacing the country’s shipbuilding and repair capabilities. Shown above is a 1966 photograph of Jurong Shipyard. (Image Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore) |

|

| The Jurong Fishery Port, established in 1969 at the former Tanjong Balai, to serve as a hub for the handling of fish imports into Singapore. This facility also functions as a marketing distribution center for seafood, featuring a wholesale fish market and various shops for the sale of seafood products. Besides handling fishing vessels from Indonesia and those operating in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, the Fishery Port also receives seafood via trucks from Malaysia and Thailand, as well as by air from countries including Australia, Bangladesh, China, India, Myanmar, Taiwan and Vietnam. Shown above is the fish market at the Jurong Fishery Port taken in 2007. (Image Credit: Photo by Benjamin Lyons via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED)) |

|

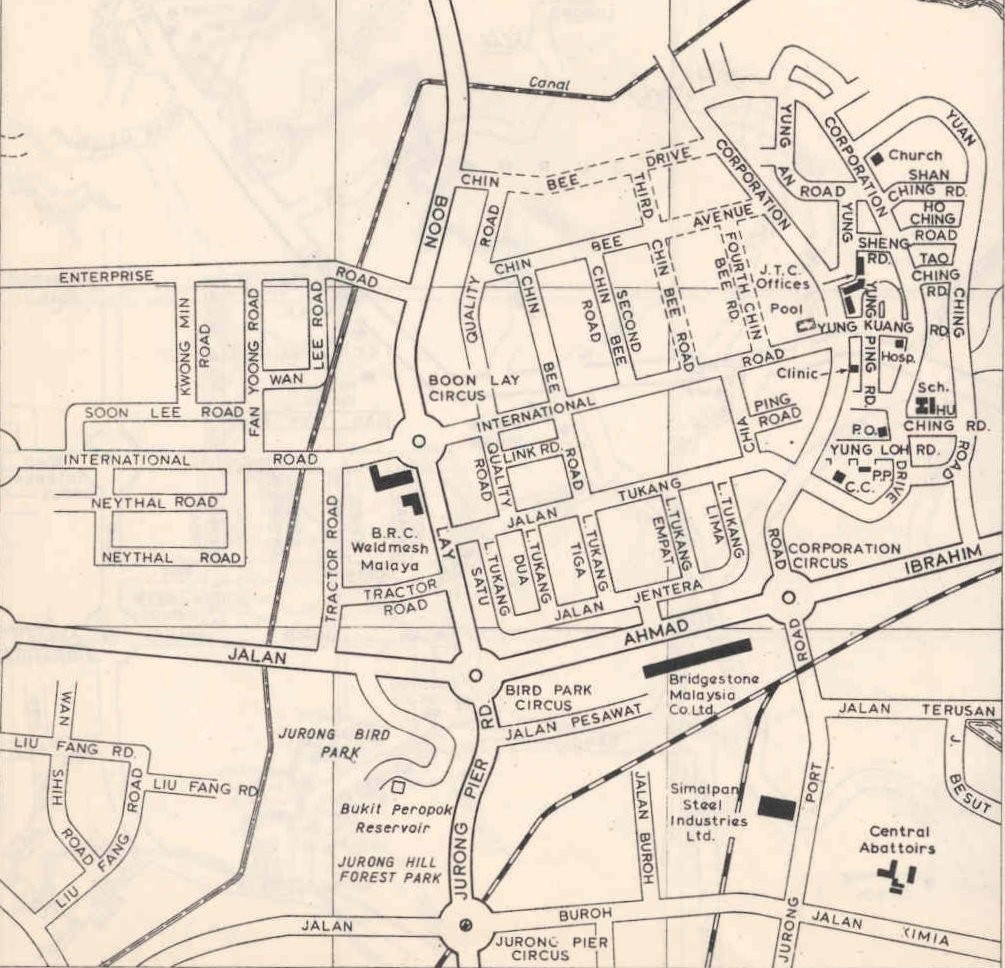

| The development of Jurong as an industrial estate in Singapore included the construction of roads, with more than 30 thoroughfares built within the first decade of its development to connect factories to port facilities, housing estates, and the rest of the island. Interestingly, these new roads were given names that reflected themes of “industry” and “progress”. For example, on the 1972 street map of Jurong, you could find roads with names like Corporation Road, Enterprise Road, Quality Road, Tractor Road, Fan Yoong Road (which means “Prosperity” Road in Chinese), Jalan Pesawat (or “Machinery” Road in Malay), or Neythal Road (or “Weaving” Road in Tamil, possibly referring to the presence of textile factories along the road). These names symbolised the industrial and economic growth taking place in Jurong. (Image Credit: Copyright © 2023 OneMap, Singapore Land Authority) |

References

Click the following PDF icon to view and download the reference list used for this page: